The real reason why some people's work never get read

There's a famous Tolstoy quote (from Anna Karenina), which goes like this:

"All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

I think about this quote sometimes when I review strategy documents or presentations at work.

Why? Because it usually holds true. The best written documents I've seen all adhere to a similar set of principles.

Meanwhile, the ones that flounder? They each tend to flounder for different reasons.

But there is one exception to this rule. Because most struggling materials still have one thing in common.

And it's the fact that they're all trying to say too much.

If you think it's about volume — think again

What does it mean to "say too much" when it comes to writing presentations or documents?

Your gut reaction might suggest the following (obvious) examples:

- Having too many pages

- Having dense or text-heavy slides

- Having really long paragraphs or sentences

These examples aren't wrong – they're just not the full picture.

Because consider the following non-obvious, yet even more damaging instances of trying to "say too much:"

- Including too many calls-to-action

- Trying to be exhaustive with examples

- Giving too much spotlight to tactical details

- Providing too many dimensions or drill-downs

So why is this an issue? Because these tendencies don't just compromise readability – they destroy it completely.

In some cases, your work may not even get read at all. Literally.

And if the thought of this makes you sweat a little bit (like it does for me) – read on.

Because here are 3 examples of what "saying too much" looks like in practice:

👋 Join 5000+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

▌ #1 Including "tangential" content.

Let me emphasize again: "too many messages" is not the same as "too many pages/slides" or "too wordy."

What matters is not the absolute length of your content (although don't treat this as a free pass to ramble) – but whether everything "ladders up" tightly and logically into your core message(s).

For example, imagine that you're writing a proposal. You're trying to influence your product stakeholders to build bespoke features for your market.

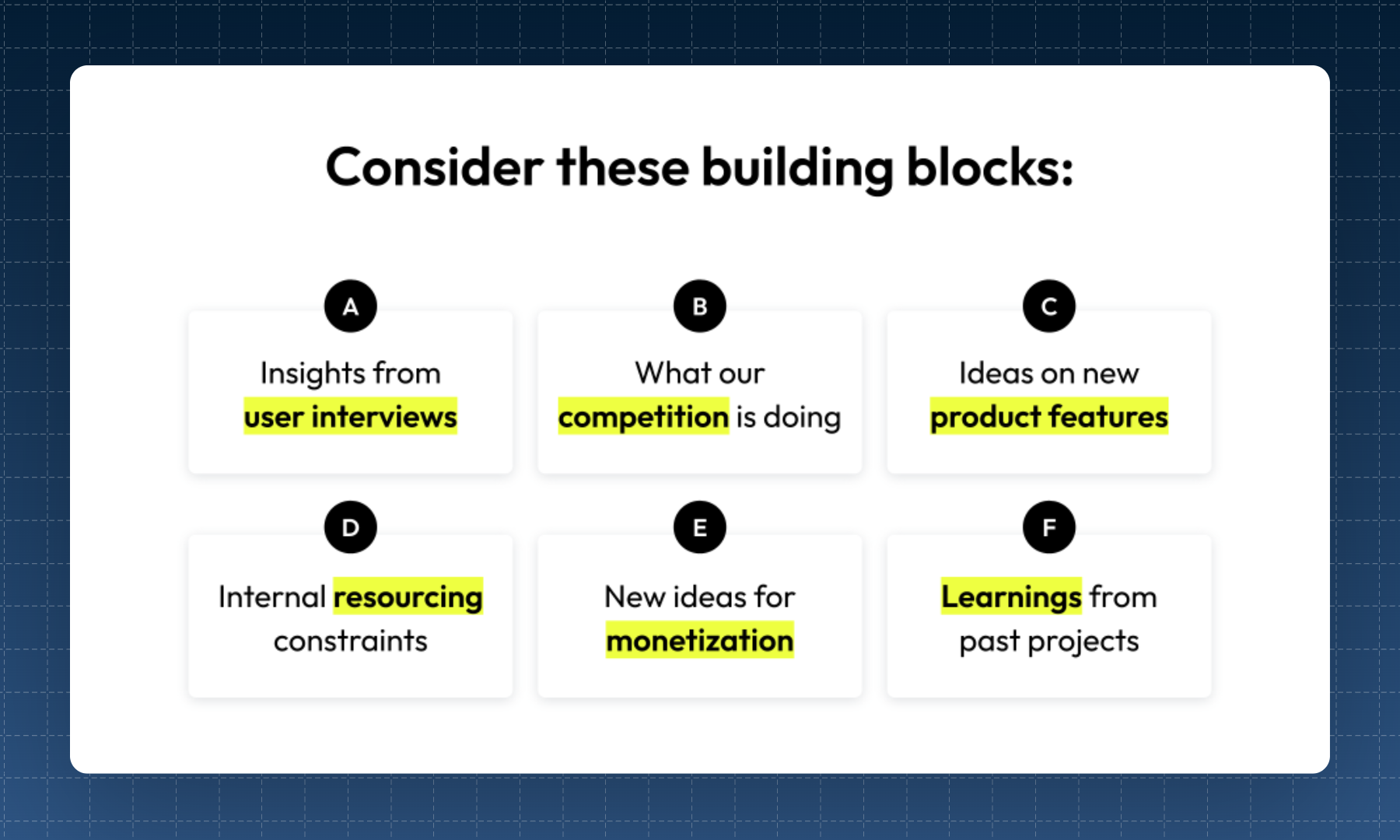

Let's say that in terms of content, you have come up with the following "building blocks:"

Now, is this "too much" content? I would argue no.

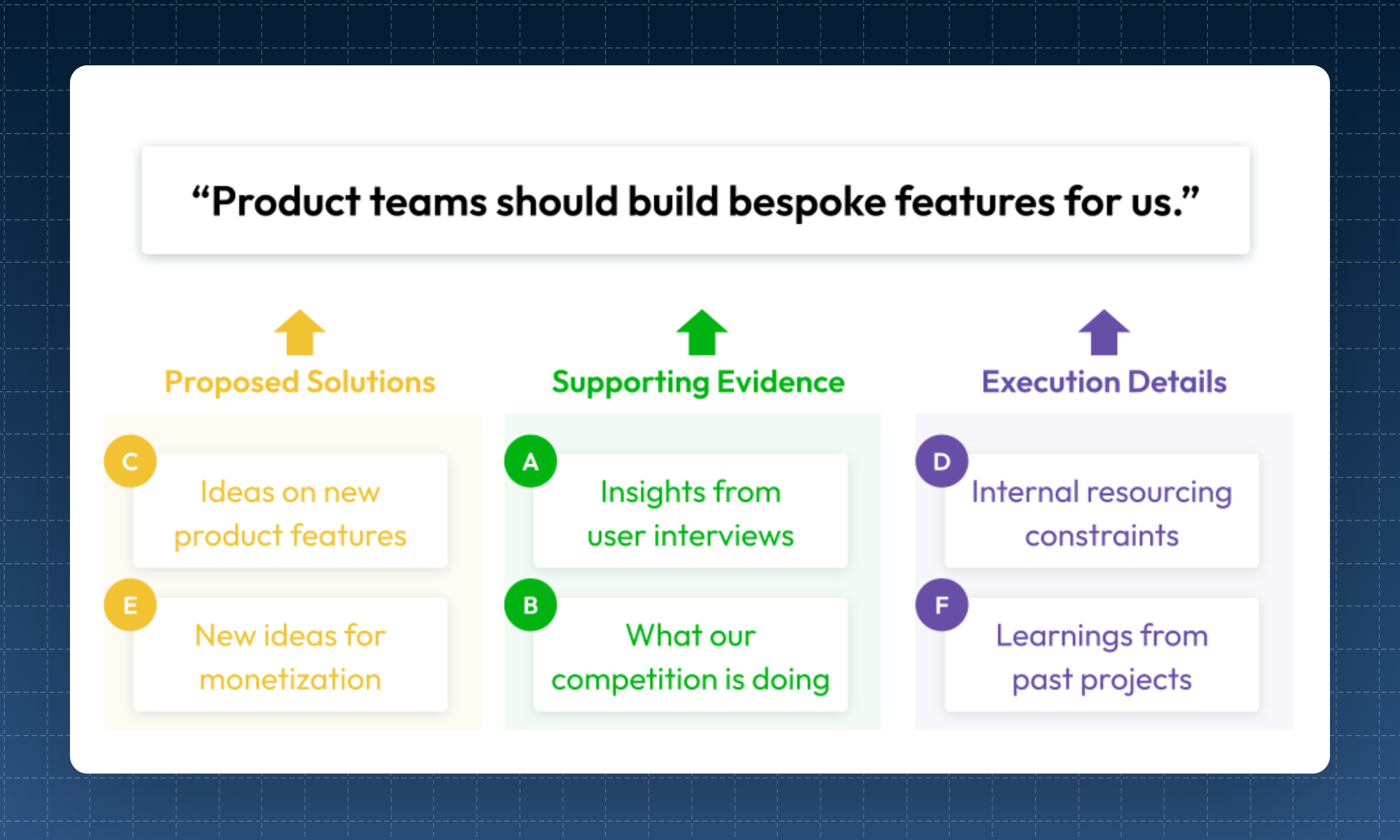

Why? Because these building blocks all "ladder up" directly into your core message. They each play a distinct and critical role.

In fact, this is easy to see once you apply the right structure and bucket the building blocks accordingly:

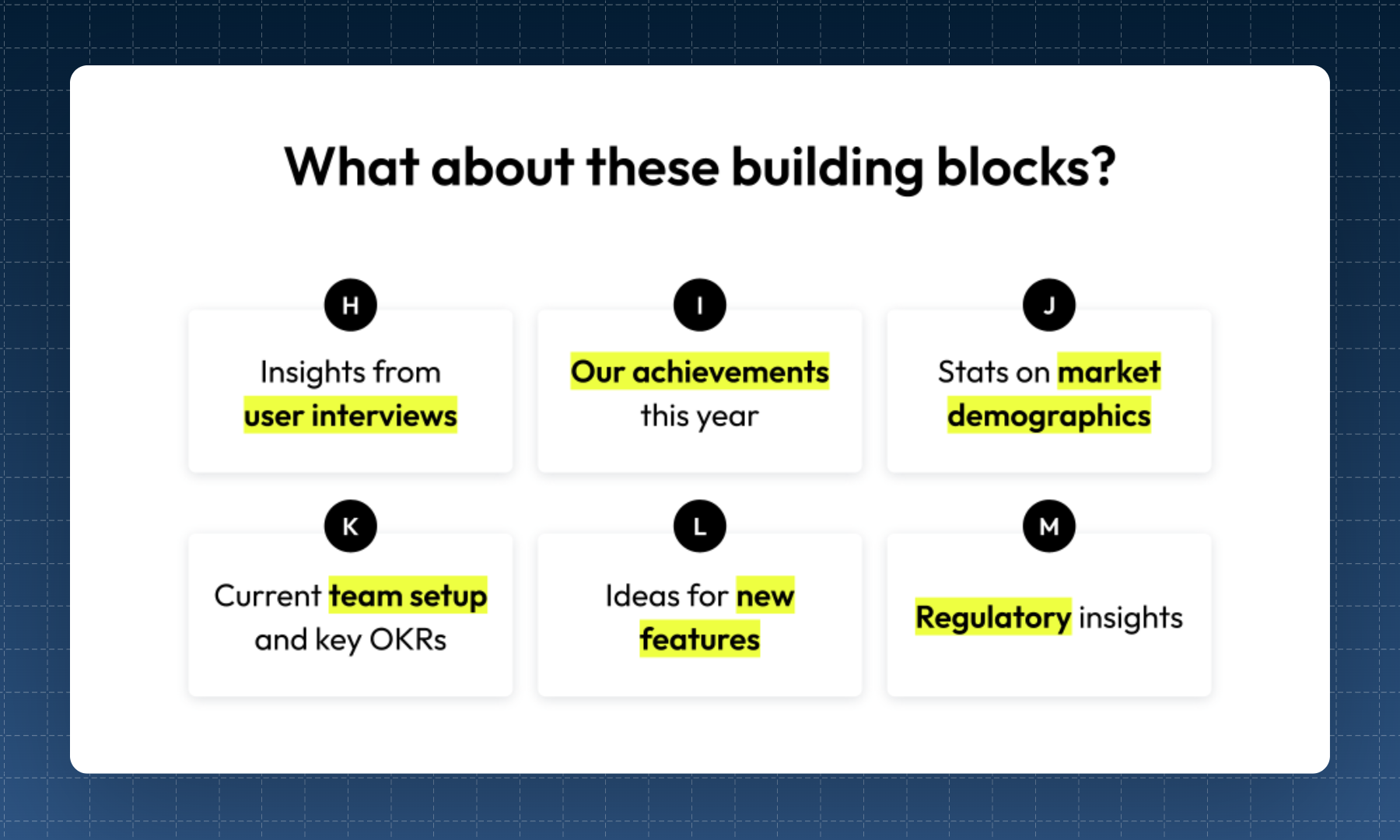

But now, consider a different set of building blocks, such as the following:

Is this "too much?"

At a glance, you might say no. After all, it seems like we're saying a similar amount of stuff as the previous example. If that one is OK – surely this one is as well.

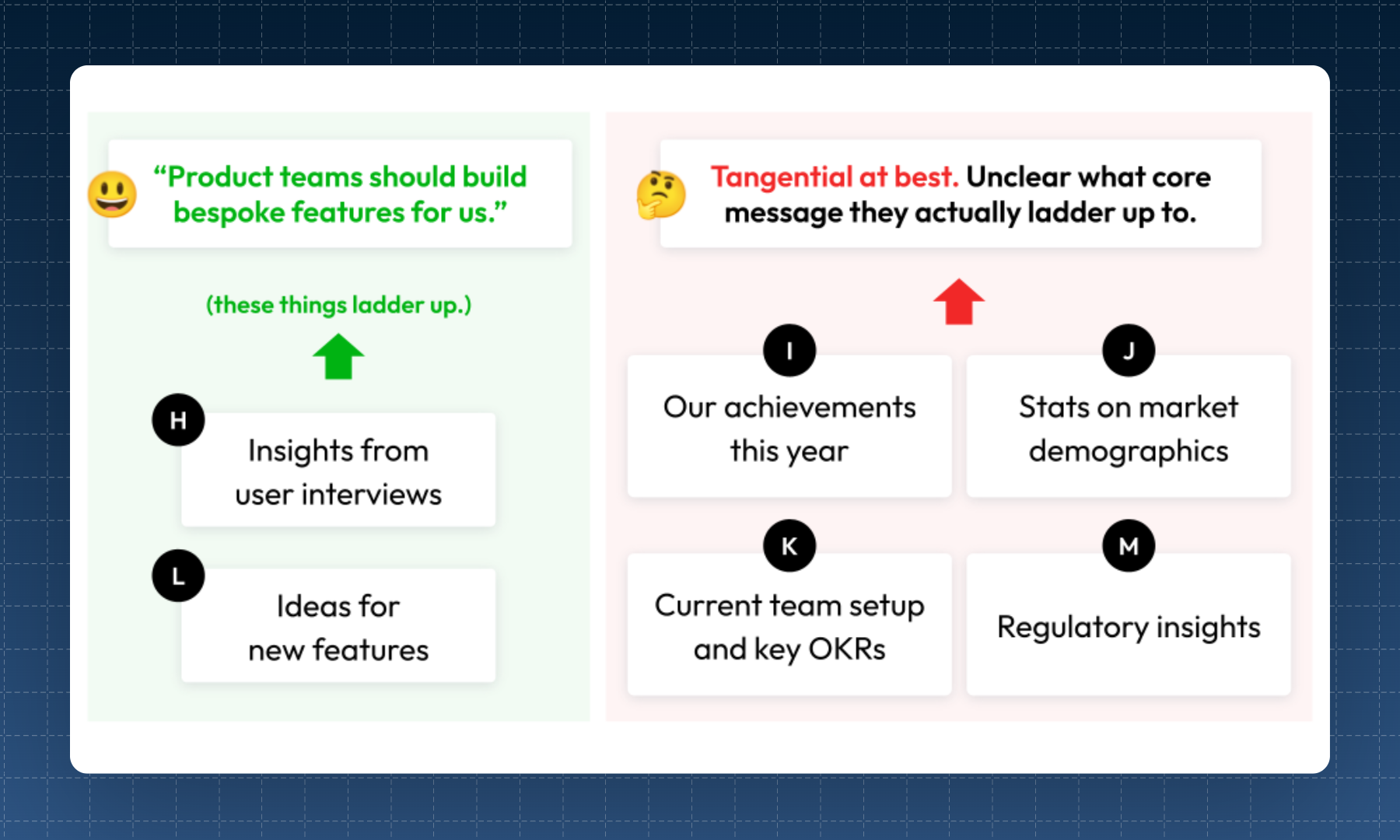

But again: it's not about absolute volume. It is about relevance.

And in this case, most of the building blocks fail that litmus test – because they simply don't "ladder up" to the core message:

To be clear: it's not that some of these building blocks aren't interesting, insightful, or important. Because they very well could be.

However, if you are laser-focused on landing your core message? You'll easily realize that some of these building blocks are tangential at best – and distracting at worst.

And when that happens – you're trying to say "too much." You compromise the readability of your work.

⭐ Want access to my favorite slide templates, cheat sheets, and storytelling tricks? It's all here — and it's 100% free.

▌ #2 Writing "laundry lists."

One of the biggest mistakes I see repeatedly is this: trying to be exhaustive when you write – and refusing to deprioritize any content.

When this happens with your written materials – you don't get brownie points for going the extra mile.

Instead, the opposite effect happens: because you have now created a laundry list.

(And no one wants to read a laundry list.)

What does this mistake look like in practice? Here are some examples:

- ❌ When providing updates: Listing out every bit of tactical detail – instead of focusing on what truly matters

- ❌ When asking for support: Presenting a bunch of disparate asks regardless of priority – instead of curating intentionally

- ❌ When presenting data: Opining on every single metric or datapoint – instead of prioritizing the most important insights

But why do people do this? Well, it's usually due to one of the following concerns:

- Fear of misinterpretation: "My topic is very complex and nuanced, and they won't truly get it if I don't tell them everything."

- Fear of offending people: "Everything we work on is really important, and I don't want to offend anyone by leaving out someone's work."

- Fear of not getting credit: "If I do not provide an exhaustive view, they will underestimate our impact and not give us proper credit."

- Fear of being seen as lazy: "If I don't go into enough detail, they will think that I didn't work hard on this, or that I don't know enough about it."

Don't get me wrong: these are fair concerns.

But ironically? If your solution is to include anything and everything – you're actually making things even worse.

Because writing laundry lists is one of the laziest things you can do. You destroy not only the readability of your work – but also your own credibility.

You're all but telling your intended readers that:

- You were too lazy to think through how to prioritize the content properly

- You want them to do the hard work and sift through uncurated content

- You haven't gone out of your way to reduce mental tax for them

And that's a terrible reputation to have.

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

▌ #3 Getting overly tactical.

If you know your stuff really well – great. But if you know your stuff too well? Be very careful.

Because in those situations? People tend to get too much into "in the weeds." They forget to zoom out.

And they unintentionally "say too much."

Why is this an issue? Because people then end up doing things like:

- They talk too much about tactical execution and operational details (instead of focusing on key outcomes)

- They focus too much on short-term updates (rather than long-term implications)

- They overuse acronyms and shorthand (and forget that it's incomprehensible to other people)

- They talk too much about things that only matter to them (and not for senior leaders with a much broader scope)

When you check any of these boxes – it doesn't matter how sharp your bullet points are, or how clean your slides look. You're still saying too much.

Let's look at an example. Imagine that you're writing an update to your leadership regarding the outcomes of a recent marketing campaign.

✅ Here's an example of a solid update:

- Outcomes: Campaign delivered 100 quality leads at 20% lower costs vs. benchmarks. This could translate into $xxK in ARR revenue.

- Learnings: Opportunity to achieve greater scale and efficiency by pooling budgets across regional teams; plans in discussion

- Next steps: Please expect an update in the next 2 weeks, as we will finalize Phase 2 plans and surface it for leadership approval.

❌ By contrast, here's a poor update that's trying to "say too much:"

- Context: We signed a contract with marketing agency X to conduct a lead generation campaign on 5 social platforms

- Results: We collected 100 leads: 20 are from Asia, 50 are from North America, 30 are from Europe

- Learnings: Weekly working group was critical to align messaging; bi-weekly reports also allowed us to adjust targeting strategies

So why is the first example significantly better than the second one? Don't they take up the exact same real estate? Why is the latter considered "saying too much?"

Well, it's because:

- The former focuses on outcomes that matter for an senior audience ("100 leads; 20% lower costs"); the latter focuses on operational details ("marketing agency X; 5 social platforms") that are trivial

- The former calls out insights that are meaningful for the wider business ("opps for scale and efficiency"); the latter tees up datapoints ("20 leads from Asia") that don't contribute to anything

- The former is forward-looking and has a clear bias towards action ("Phase 2 plans"); the latter talks about tactical details that no exec would care about ("weekly working group; bi-weekly reports")

So again – it's never simply about volume. It's about whether you're saying things that actually matter.

👋 Join 5000+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

Quick recap

- If you have a habit of "saying too much" when you write – know that your work is at risk of not being read at all.

- So what is "saying too much?" Common examples: surfacing tangential content; building laundry lists; getting too tactical.

- Remember: the answer is not simply to just "keep things short." It's about saying (and only saying) things that matter.

Other helpful materials

To uplevel your writing further and land outcomes that you want, here are some more resources you can leverage:

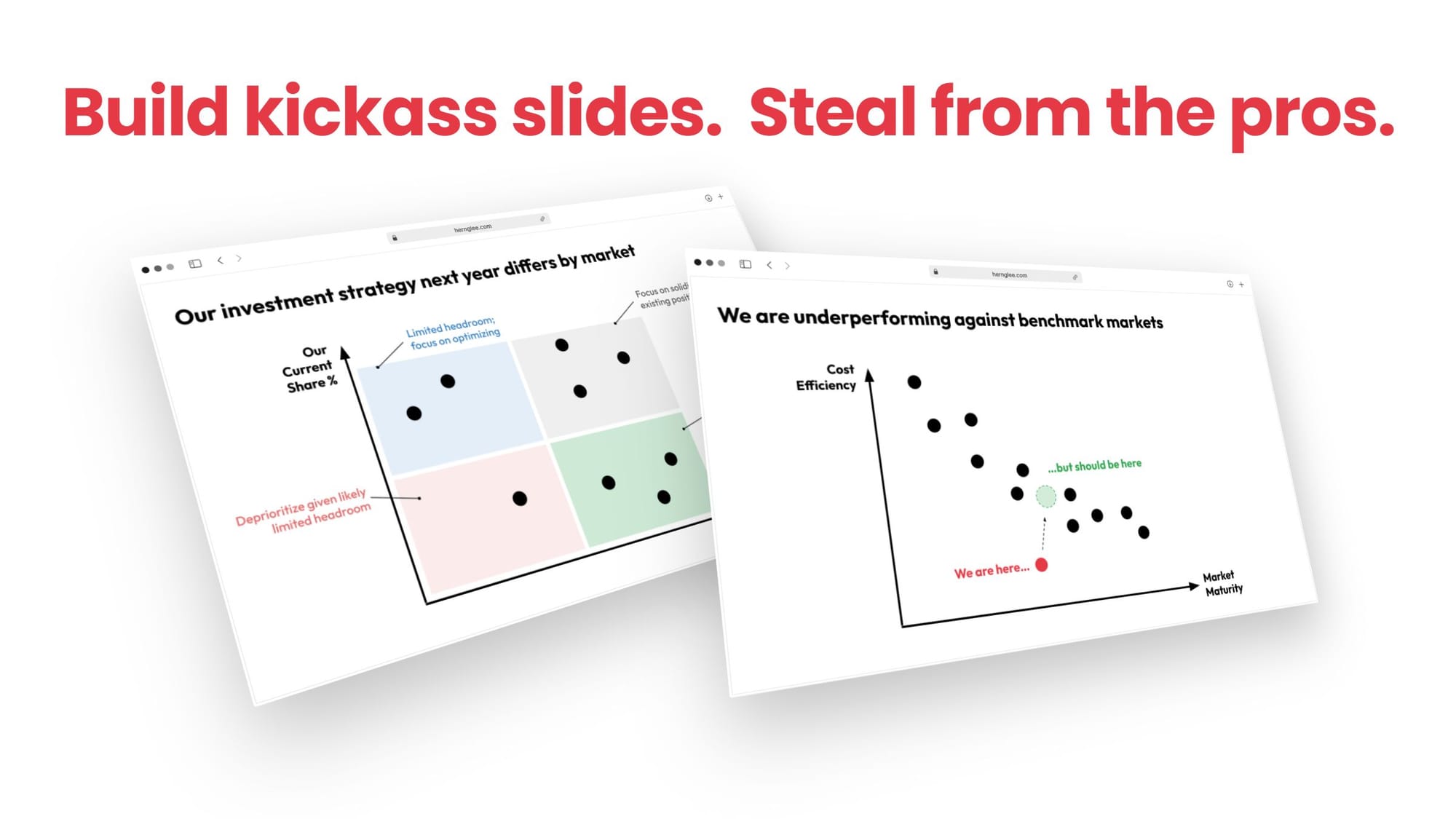

- How to build exec-ready presentations (50-slide playbook)

- How to avoid self-sabotage from unintentional signaling

- The "Goldilocks" principle of writing strategy plans

- How to write in a "polished" manner at work

- 5 "tricks" to use for effective storytelling