What Goldilocks taught me about writing strategy plans

I've read many strategy documents and business plans over the years.

And the best ones I see? They have one thing in common:

They authors all tend to adhere to the "Goldilocks" principle.

(Let me explain.)

👋 Join 4900+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

What is the "Goldilocks" principle?

You might recall the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

If not, here's the speedrun version:

- 3 bears lived in a house in the woods: Papa Bear, Mama Bear, and Little Bear

- Goldilocks accidentally went into the house one day, while the bears were out

- So she ate their porridge, sat in their chairs, and slept in their beds

But here's the thing: Goldilocks did not find either Papa Bear's or Mama Bear's stuff satisfactory.

Because Papa Bear's porridge was too hot, his chair too hard, and his bed too high.

And Mama Bear's was the exact opposite: her porridge too cold, her chair too soft, and her bed too low.

But Little Bear's stuff? It was "just right" in everyway.

Finding your "little bear"

When you write a strategy document – keep the Goldilocks principle top of mind.

Because much like Goldilocks's affinity for Little Bear's stuff? We want to find that perfect balance as well.

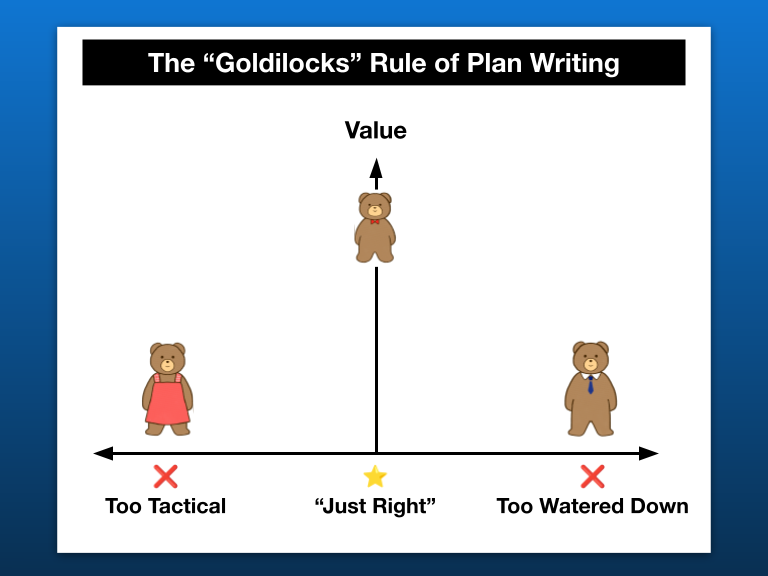

The 2 mistakes I often see with strategy documents at work?

It's either drilling down too much, i.e. being too tactical and treating the plan as a laundry list of to-do's...

...or watering things down too much, i.e. chasing simplicity at the expense of specificity.

Or, if you can't bear all this text (I'm so sorry) and want a visual instead:

Let's talk about the left-hand side of the spectrum first.

What does it mean to get too "tactical" when it comes to plan-writing?

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

What "too tactical" looks like

When you drill down too much, you don't end up with a strategy. You end up with a tactical plan.

What is a tactical plan? It's one that spells out everything you plan to do, without any attempt to:

- Consolidate into themes

- Anchor via frameworks

- Weave into a narrative

Here's the thing: plans are meant to be digested, socialized, polished, and executed.

So if your plan is complex, unorganized, or even tedious? It doesn't necessarily mean the strategy is bad.

But it does mean that it's less likely to "stick" for others.

Then it doesn't matter how insightful your content is by that point.

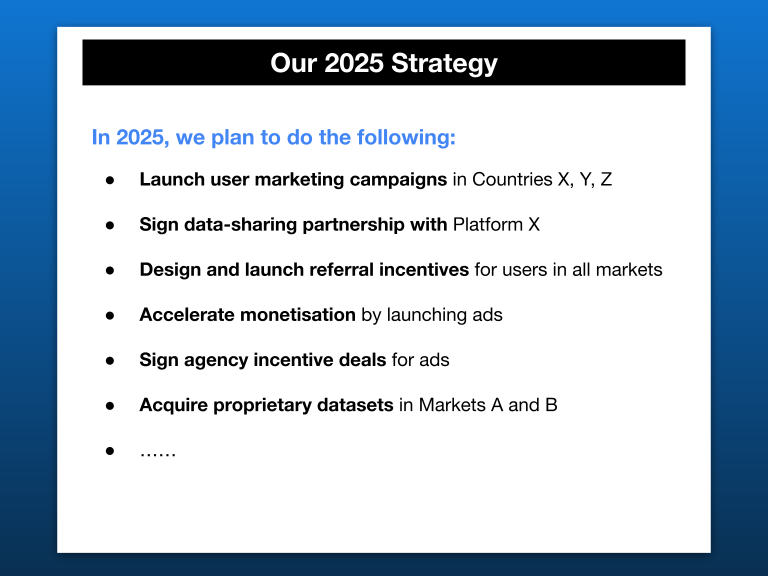

Consider, for example, the experience of reading a plan like this:

This is (the start of) a fairly decent plan. There's specifics around what the team intends to do, and how the team plans to do it.

The problem? It's a laundry list. It doesn't quite "stick."

Besides, there's no unifying framework around why these are the right things to do. It's not apparent why you wouldn't do more (or do less).

This is often the problem that I see with some strategy documents. The raw material is often great and well thought out – but the delivery falls flat.

Because the audience is given a grocery list – and not a coherent narrative. It doesn't stick. And it often struggles to persuade.

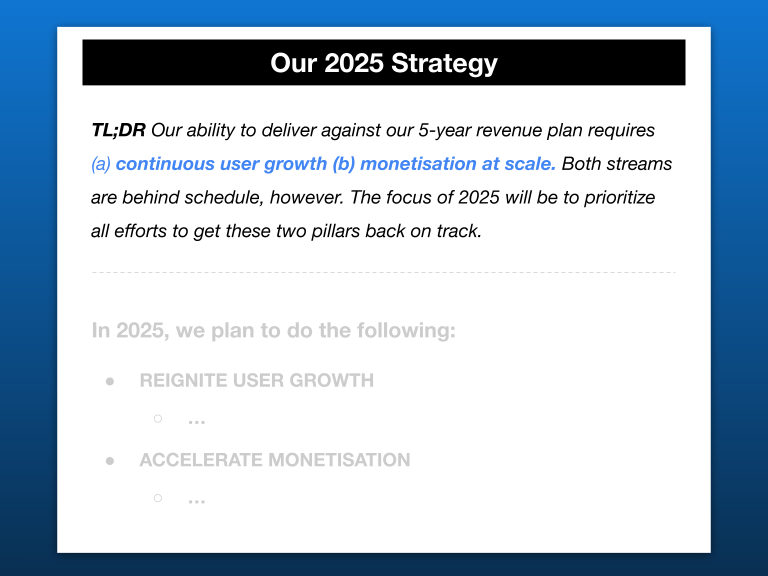

But consider a few ways in which the author could "tighten" up the plan by "bubbling up" the key themes:

There's no rocket science here – it's just bucketing and categorizing. But the readability (and "stickiness") improves tremendously.

In fact, besides simply "bucketing" – the author might even take it a step further by contextualizing the strategy:

Notice how this little preamble helps establish the framework for what's about to follow. It sets the scene for why everything stems from these two pillars – not more and not less.

And these are the kinds of strategy documents that actually "stick."

Let's now talk about the opposite problem: watering down too much.

👋 Join 3500+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

What "too watered down" looks like

A good strategy document cannot be a tactical laundry list. But that doesn't give you permission to overcorrect either.

The problem I see often (especially in a slide-heavy environment)? Optimizing for storytelling simplicity, at the expense of critical thinking and specificity.

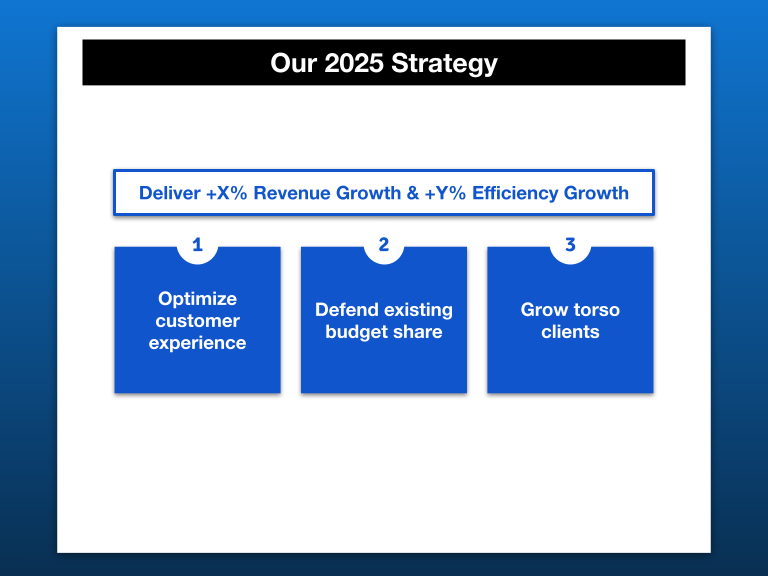

For instance, consider a strategy slide that looks like this:

What you're seeing is a piece that has optimized so much for readability – i.e. watered down so much – that it can hardly qualify as a strategy document.

But what if this is followed by other slides with more detail? Surely that makes it better?

Not really.

Because the fundamental problem with this framework isn't its simplicity – but rather the lack of critical thinking.

Consider the following issues:

- Firstly, where's the "how" in all of this? For example, how do you plan to grow torso clients? Is it by offering better incentives, finding new ways to cross-sell, or launching targeted marketing campaigns – or all the above?

- Secondly – and this is a common mistake – growth is the outcome, not the lever. Simply replacing "revenue growth" with other verbs ("defend share," "capture headroom," etc.) doesn't cut it either. You still haven't explained your actual strategy.

In other words: there's nothing wrong with simplicity when it comes to your narrative. As long as you can make clear how you're going to get there.

But if you don't have a good answer?

You might as well just say your strategy to make more money is to make more money.

(Don't laugh – you'd be surprised at how often tautological fallacies appear in strategy documents!)

The point is this: there is tremdnous value in being able to distill complex thinking down into digestible themes. After all, that's the only way you can land your narrative and secure buy-in.

But you cannot do it at the expense of specificity, actionability, and accountability.

You have to find your "Little Bear" – and get the balance just right.