Why "be more strategic" is useless advice

Here's my guess: most people have had the following experience at work.

You work on something, send it out for feedback, and you get comments along the lines of:

- "Can we make this more strategic?"

- "Can we uplevel this a bit more?"

- "Can we make this more exec-ready?"

But here's the thing: while the feedback is almost always valid – most of the time, we have no idea what the other person actually means.

And to make things worse? We feel uncomfortable clarifying why.

(After all, who wants to appear dumb and imply that they can't tell what is "strategic," and what isn't?)

And so, as a result: we politely acknowledge the feedback, without really knowing what to fix.

We simply trim things down a bit, swap in some big words – and pray that the next iteration will land.

Of course, while I say we – I really mean me. Because this was my struggle for the longest time.

And it took me years before I figured out what it meant to "be more strategic" – and why there are far better ways to say it.

👋 Join 5000+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

Stop using the word "strategic," unless...

Let's be clear about one thing first: there's nothing wrong with recognizing that a piece of work wasn't built with a strategic lens.

But the problem with simply saying something doesn't feel strategic? It becomes a cop-out mechanism. You know that something feels "off" about a piece of work, but you can't articulate exactly why.

And our feedback fails to actually fixes the issue.

Therefore, if you're the one giving the feedback? Drop "strategic" from your vocabulary altogether.

Stop saying "it's not strategic enough." It doesn't help anyone.

And instead, ask yourself if what you really meant was:

- It's too tactical.

- It's tautological.

- It's short-sighted.

- It's ambiguous.

- It's not focused.

And in today's issue – we'll talk about what to do if you find yourself in these scenarios.

#1 Say: "It's too tactical."

What does it mean to communicate in a way that's "too tactical?" Let's illustrate with an example.

Imagine that you are a basketball expert, and your friend Bronny has asked you to build a plan to help him become a professional basketball player some day.

Let's say you've prepared an awesome plan. How do you communicate it?

Well, it turns out that the same content can be communicated very differently, and land very different outcomes.

❌ Because this is what an "overly tactical" plan looks like:

- Run 5KM every day

- Lift weights 3 days a week

- Make 1000 3-pointers every day

- Watch one hour of game film daily

What's wrong with this plan? Well, nothing really. For all we know, these might actually be all the right things to do.

But that's precisely the issue: it feels like a bunch of "stuff." It feels like an arbitrary set of motions and activities. It feels like the outcome of strategizing, while the rationale behind it is nowhere to be seen.

No wonder it doesn't feel "strategic" for some reason.

✅ But consider what a "less tactical" strategy could look like:

- Achieve NBA-level athleticism (by going to the gym x times a week, and ... )

- Carve out a niche as a 3-point specialist (by making X shots a day, and... )

- Compensate for lack of size with passing skills (by watching game film, and...)

The difference? When you communicate strategically, you're guided by higher-order thinking. You're not just focused on the how – you're also focused on the why.

You're able to articulate the upstream principles behind the tactical motions.

A common mistake I see people making? It's to assume that "being strategic" means that you never talk about tactics or details.

But this is false – details absolutely matter. Having principles yet lacking a plan for execution is useless.

So instead, a better way to think about it is this: it's not about how much detail you're "allowed" to surface.

It's about training your brain to think of activities as outcomes based on a set of principles – rather than starting points.

As long as you do that – you have a higher chance of landing your message. Then you have every right to talk about tactics alongside your guiding principles.

Remember: being tactical is not always a bad thing.

It just cannot be the only thing.

#2 Say: "It's tautological."

In an attempt to make their strategies sound "smart," people tend to make another mistake.

And that is using different ways to describe the same thing – and mistaking it for strategy.

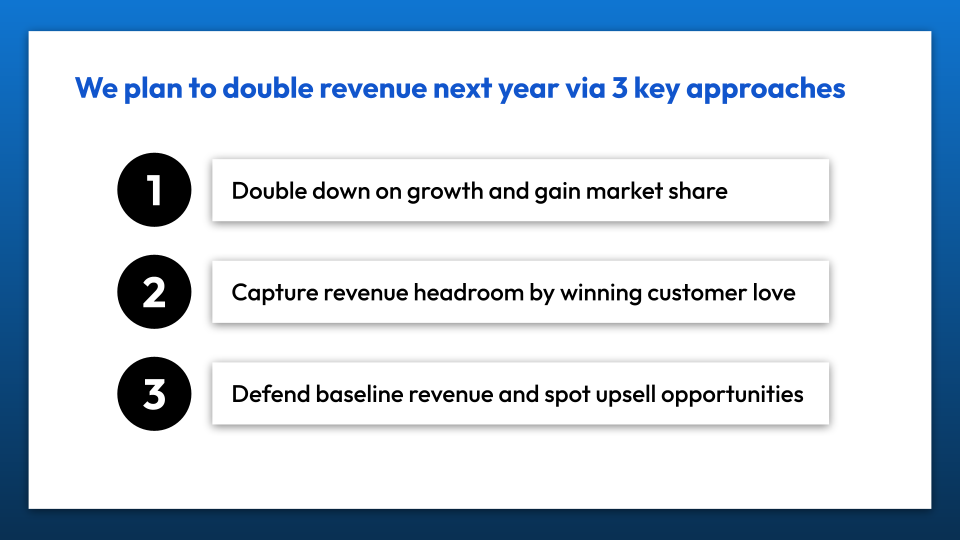

For instance, consider the following "smart-sounding" business plan:

At a glance, everything seems reasonable – except something feels off.

That something? It's the fact that this slide actually says nothing of substance. The 3 "strategies" mentioned here are completely tautological.

It's the equivalent of saying "we're going to get rich by making more money."

So how do we avoid making this mistake? There's a couple ways.

The first is to force yourself to use the simplest language you can to describe what you're saying.

Because once you remove the distraction of buzzwords and corpspeak? It's much easier to catch yourself when you're committing a logical fallacy.

The second is to "flip" your narrative around, and ask yourself if there's ever a situation where the counterargument holds true. For instance:

- "Would we ever NOT want to gain market share?"

- "Would we ever NOT want to win customer love?"

- "Would we ever NOT want to spot upsell opportunities?"

After all, if it can never really be untrue – it's not really a point of view.

(Related read: What does it actually mean to have a "strong POV?")

#3 Say: "It's short-sighted."

Being "strategic" isn't just about linking inputs ("I'm going to work longer hours") with outputs ("in order to close more sales") and avoiding tautological fallacies.

It's about identifying and establishing non-obvious relationships.

And the inability to do so? It results in situations where a plan seems to check all the boxes ("If we do X, we will achieve Y") – but still feels less than strategic.

For example, imagine that we're building a plan to double revenue next year.

Here are some ideas that are perfectly reasonable, yet somewhat short-sighted:

- Ask our sales teams to pitch more often

- Track revenue trends more frequently

- Prioritize serving the fastest-growing accounts

The reason these ideas don't feel "strategic?" It's not because they're tactical or tautological.

Rather, it's because they're just not very insightful.

They feel like the equivalent of asking a basketball player to get better at shooting... by practicing more.

(Well, sure. But also – duh!)

By contrast, consider the following ideas*:

- Develop affiliate sales channels to scale faster through partners

- Experiment with bundle pricing to increase average order value

- Redeploy offline budgets into online channels for efficiency

Look, these ideas may or may not move the needle. They could very well backfire as well.

But the point is this: there is at least an attempt at establishing non-obvious relationships. An attempt at finding levers that could result in step-change, rather than marginal improvements.

Sure, that doesn't automatically make these ideas "strategic." But I'll take them over the first set of ideas on any given day.

* Of course, this is not necessarily a fair comparison, given the latter set of ideas requires a wider set of levers. But the point stands!

#4 Say: "It's ambiguous."

Sometimes, it's not about how strategic or how insightful a given piece of content is.

Rather, it's the lack of precision that makes something come off as suboptimal.

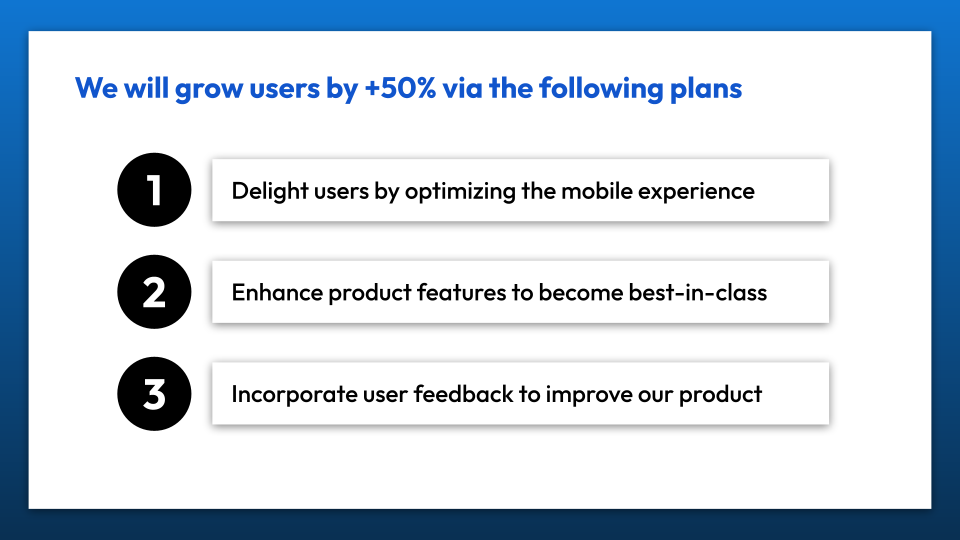

For instance, consider the following one-slider:

While we shouldn't really judge a book by its cover, it's hard to imagine anything insightful following this slide.

Why? Because all 3 bullet points are highly ambiguous.

No one is expecting a play-by-play breakdown, of course – but there's a minimal level of precision and specificity you always need to achieve.

Saying things like "enhancing product features" or "improving our product" just doesn't help. These phrases are ambiguous, generic, and underwhelming.

Even if you actually have specific ideas mapped against these buckets, you might lose your audience before you even get started.

(Related read: For more on finding the right balance between specificity and digestibility, read what Goldilocks taught me about writing strategic plans)

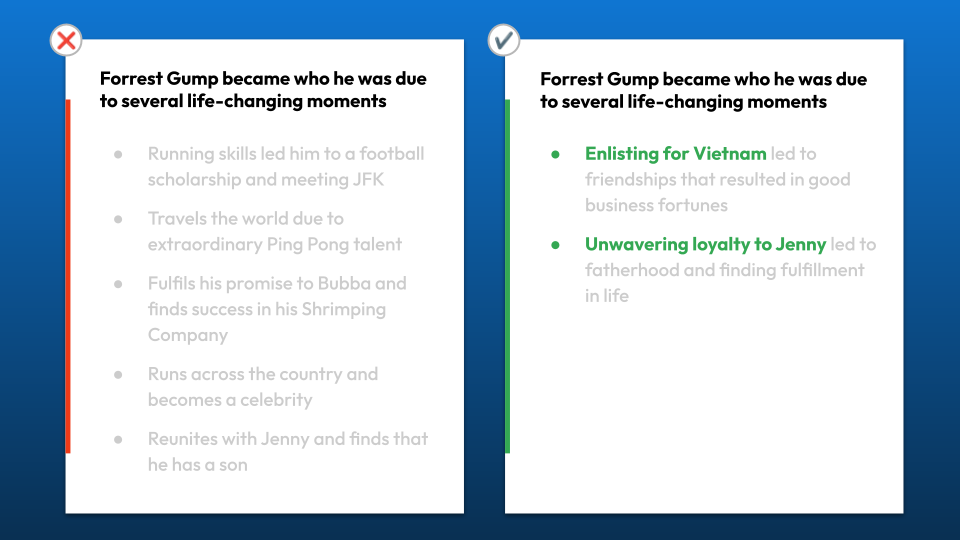

#5 Say: "It's not focused."

There's a well-known quote by Michael Porter that says strategy is all about trade-off's.

The implication of this? It's that you really can't claim to be thinking strategically, if you decide that your plan needs to include everything.

But this is something that plagues many plans, where there's no attempt at making trade-off's. Every idea, every caveat, and every bit of context seems just important enough to include.

Sooner or later, you end up with an unwieldy and unfocused document. And it comes off as not very strategic.

The key to fixing it? Sometimes it's rather easy. Because it's not really about how strategic your ideas are.

Rather, it's about how good you are at staying focused, and deprioritizing ruthlessly.

For instance:

(P.S. – this example is lifted from my 50-page slide science playbook, which covers 24 principles on how to build exec-ready slides. You can grab it directly.)

What we see here is an example of deliberate prioritization. We're not saying that the stuff we left out doesn't matter. We're simply trying to be extremely focused, to avoid diluting our own message.

So when people say something doesn't feel "strategic?" You don't always need to go back to the drawing board and look for big ideas.

Because sometimes, it's just that you're not focused. And that makes perfectly valid content come off as subpar.

🧠 Thanks for reading Herng's Newsletter this week! If this was forwarded to you and you'd like to receive future issues, subscribe for free here.