Your inability to handle "grey" is holding you back

I attended a storytelling workshop once during my second year at Google.

The workshop was fantastic. There was a heavy focus on data visualization, and I picked up many practical tips on how to make my slides stand out.

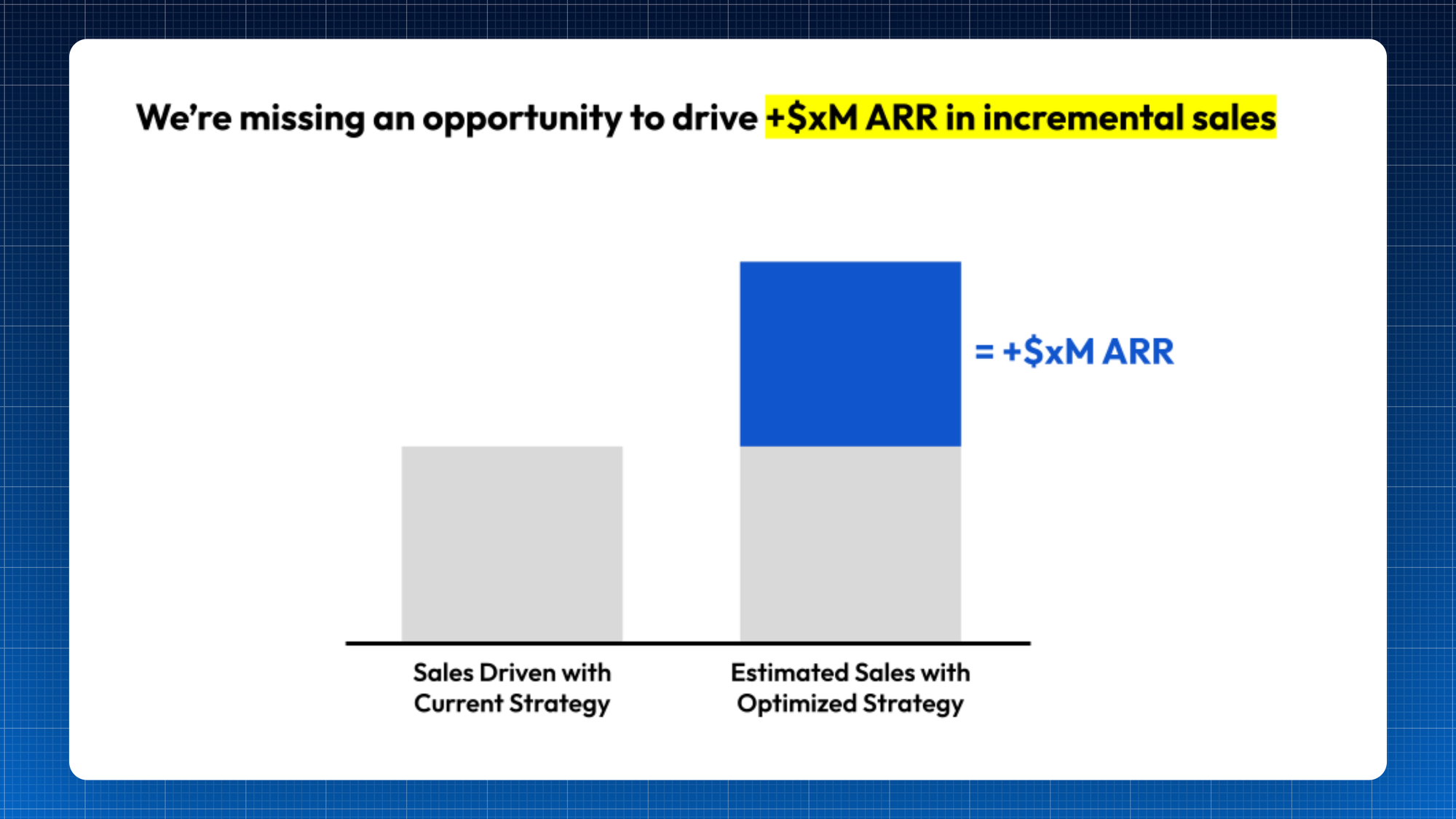

In particular, there was one visual that blew me away. I couldn't stop thinking about it – even long after the workshop.

It was something to the following effect:

I fell in love right away with the minimalist visual and the powerful narrative. Because how could anyone say no to a pitch like this? It was the money slide of money slides.

(And I couldn't wait to make all my slides look like this.)

So in the months that followed? That's exactly what I aimed for. I tried...

- ...looking for "slam dunk" insights in my analyses

- ...centering my narratives on big, impressive numbers

- ...building slides in a way so I could have a "mic drop" moment

Because as I freshly learned? Storytelling was about distilling complex analyses down into something brutally simple.

Or so I thought.

👋 Join 5000+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

The limitations of simplicity

I was glad to have attended that storytelling workshop. But in retrospect, I was glad to have attended it early on in my career, so I could "get it out of my system."

Because while simplicity is a fantastic outcome (and takes a lot of finesse to achieve)? The hard things are rarely simple.

And the more senior you become – the harder the problems get. Gone are the money slides and slam-dunk narratives. A lot more "grey" awaits instead.

(That's a good problem to have in your career, of course.)

And that brings us to the crux of today's issue – which is that most people over-chase simplicity when it comes to influencing at work.

Sure, they know how to communicate when storylines are simple, when numbers are big, or when the narrative is a no-brainer.

But for anything remotely "grey?" They struggle. They then end up either communicating ineffectively, or misrepresenting the truth.

For example, here are what "simple" storylines tend to sound like:

- "If you purchase our services, we will deliver incredible ROI for you (and here's how we can prove it)..."

- "If we don't invest in XYZ opportunity today, we'll miss out on this much $$ – therefore we need to take action right away..."

- "We did an incredible job last year with this campaign, and this year we want to go even bigger, and here's why we deserve funding..."

But in reality? Most narratives aren't so easy or straightforward. Instead, they tend to resemble the following:

- "We know that our current proposal isn't perfect, but here's how we can still minimize the risks while mostly addressing your key objectives..."

- "We don't have a perfect option in front of us, but we recommend going ahead with Option B (even though that creates other issues), and here's why..."

- "We need support for XYZ project – but yes, we do have a backup plan if support doesn't come through. However, it's an imperfect backup plan, so here's why we're still asking for support..."

None of these are "no brainer" messages. I can't envisage corresponding "money slides" that will blow people away either.

But to become a great operator: you will need to find ways to communicate such ideas clearly and effectively – without losing nuance.

And for people who can't? It tends to result in some of the following behaviors (they may seem unrelated, but they all stem from an inability to deal with nuance):

1️⃣ Inability to articulate assumptions.

People who over-chase simplicity tend not to think deeply about the implicit assumptions behind their claims. They draw questionable conclusions as a result.

Because here's the kind of "straightforward" stories they want to tell:

- ❌ "If we deprioritize these 3 workstreams, that gives the team more time to meet customers, which will allow us to grow the business. Therefore, let's drop these 3 workstreams."

In reality, here's what they should be thinking instead:

- ✅ "What do we need to believe for this to be true? Are we expecting the team to meet more new customers, or engage existing ones more deeply? Are customers really not spending more with us simply due to lack of engagement? Where's the evidence?"

Remembering to articulate (and even challenge) your own assumptions is hard. In fact, it can feel very uncomfortable – because you're supposed to be able to "skip that step" by relying on experience!

But the best operators don't use that as an excuse. Their pattern recognition skills are as good as anyone – but they always think in first principles to ensure their assumptions remain sharp and valid.

Let's look at another example.

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

2️⃣ Overselling.

There's selling – and then there's overselling. And it's often characterized by the overuse of hyperbole, which is one of the easiest (but also laziest) ways to engage in persuasion.

For example:

- ❌ "We absolutely need to invest in this deal – otherwise we're losing out on a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity."

- ❌ "Everything we're working on is a top priority, and we can't drop anything. We can only take on new stuff if we get more funding."

- ❌ "This request is extremely urgent since it's going to leadership; we need to drop everything else and get this done ASAP."

It's not that you can never pound the table when you truly believe in something. It's just that most situations are never as critical or as urgent as people make them out to be.

But many people still default to hyperbole, because they don't know how to communicate effectively when things are high-priority (but not critical) or time-sensitive (but not urgent).

That's a shame. And it can lead to erosion of trust very quickly.

3️⃣ Fuzzy attribution.

If you're used to "simple" storylines, you tend not to think about the counterfactual. You also tend to ignore the concept of attribution and incrementality (because, well, it's really hard).

And that's a big red flag.

For instance, consider the following claims:

- "I joined my company in 2015. Since then, I have helped the company's stock price more than quadruple."

- "I started cheering for the Boston Red Sox in 2003; due to my fandom, they proceeded to win the World Series in 2004."

- "We increased our marketing budgets by 10% last year; as a result, we helped double revenue this year."

Statements #1 and #2 are obviously ludicrous. But you hear statements like #3 all the time at work. Why?

Well, because it's simpler. And more convenient (especially if you want to claim credit).

By contrast, it's much harder to communicate what's actually happening in reality, which tends to be a mixed bag of artifacts, e.g. –

- "There is anecdotal evidence in select markets that our campaign left a very strong impression with users..."

- "There is also non-trivial sales uplift observed in certain product lines (despite the data being noisy due to holiday periods)..."

- "However, we can't rule out that some of it might be due to the impact of the snafu that happened to Competitor X during Q1..."

- "All in all, our conclusion is that our marketing campaign delivered sufficient ROI, and it is worth investing again this year, but there are some caveats..."

This is when you absolutely need next-level finesse, in order to take a laundry list and turn it into a sharp, concise, yet nuanced point of view.

Yes, it's really hard. But oversimplifying is just not the answer.

4️⃣ "Make money good; lose money bad."

An unfortunate side effect of getting too used to "simple" storylines? It's that you run the risk of becoming a myopic thinker over time.

In fact, the most dangerous thing is when people start making decisions with the following heuristics:

- For something to be "good" – it must make a lot of money

- And if something doesn't make a lot of money – it must be "bad"

This is a dangerous way of thinking – because most decisions just aren't that simple.

For instance, imagine that you're assessing an initiative that doesn't generate immediate commercial returns.

Sure, you might be tempted to write it off and shunt it aside. That's the simple and easy way to think about things, after all.

But what if...

- ...it's an experiment to generate learnings? What is the value of those learnings (which will prevent costly mistakes in the future)?

- ...it's a defensive play to reduce future risk? How do we estimate the value of that (given the counterfactual is hard to prove)?

- ...it's a move that might create indirect value for other teams? How does that change our decision principles?

- ...it's a bet that might pay off, but only in the best case scenario? And what if that scenario is possible but unlikely? Is it still worth it?

- ...it's a move to improve execution velocity? How do we assess the value of that?

All of these considerations are extremely valid. And none of them are likely to have slam-dunk answers.

But if you simply operate with a "make money good; lose money bad" mental framework? You won't even get this far.

👋 Join 5000+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

Parting Thoughts

There's no silver bullet. But the best operators tend to do a few things to help them process (and communicate) complexity.

The first is a strict adherance to structure. The content can be complex – but the communication structure need not be. Simple habits like leading with the conclusion or ensuring tight storylines can go a long way.

The second is a knack for precision. The more nuanced the situation – the more precise and efficient you want to be when you communicate. Because you simply cannot afford not to.

The third is the practice of basic comms hygiene. Little things like leveraging verbal cues or sounding "dumb" at the right moments can greatly reduce mental tax for the audience.

And if you're able to pull these levers – you'll have a better shot at landing your message. Even if it isn't simple.