What leaders expect when they read your work

What's one of the "highest-ROI" skills you can pick up at work, regardless of your background?

It's learning how to write in an exec-ready manner.

Why? Because it's one of the best ways to extend your sphere of influence.

In fact, if you can be trusted to consistently build materials that are fit for leadership consumption, here are some good things that can happen:

- Your credibility increases when you advocate for stuff

- Your leaders feel confident representing you & your ideas

- Your presence scales – even without you being in the room

- You might even get opportunities to write on behalf of leadership

The last one is especially valuable. Because when you're in a privileged position to help leaders crystallize their thinking?

You get to learn how they think. And it's amazing how much personal growth you can uncover as a result.

But to go from the "outside" to the "inside?" We need to nail the basics. We need to learn how to write to leaders, before we can write for them.

So what qualifies as "exec-ready" writing then?

Let's start first by establishing what it isn't.

Here are 3 common mistakes that prevent perfectly good content from being considered exec-ready:

👋 Join 4900+ readers and subscribe to Herng's Newsletter for free:

Mistake #1: Burying the lede

Building materials intended for executives can feel overwhelming. After all, execs aren't necessarily in the weeds, and often don't have as much context.

As a result? A common mistake is to bias towards over-explaining and over-setting the context. You feel compelled to give a history lesson before teeing up your core message – lest your leaders misunderstand.

But this is misguided – you're burying the lede. You'll lose your executive's attention before you even get to the chase.

So instead? You want to apply Barbara Minto's Pyramid Principle. Which means that you:

- Lead with your conclusion or ask first

- Give an overview of supporting arguments

- Surface the evidence that backs up these claims

As Minto put it: "You think from the bottom up, but you present from the top down."

Mistake #2: Thinking short = simple = clear

Another common mistake when it comes to preparing exec-level comms? Thinking that the less text there is, the more "high level" it becomes. Which makes it more "exec-ready."

But that's simply not true. In fact, some people overcorrect. They end up:

- Writing choppy bullet points that are ambiguous, rather than crisp

- Neglecting to contextualize, when actually imperative to do so

- Jotting down buzzwords, instead of fully-formed thoughts

The thing to realize is this:

- Short ≠ Crisp

- Simple ≠ Precise

- Brief ≠ Digestible

Yes, sometimes less is more.

But sometimes? Less is just incomplete and confusing.

(Related: this principle is especially critical when it comes to writing headlines. See examples by grabbing my slide science playbook below 👇)

Mistake #3: Lacking (even an implied) call to action.

There should be very few instances where you're presenting to senior leaders just for the sake of "updating" them, i.e. with no implied next steps.

Why? Because senior leaders are there to help make things happen. You don't go to them for tactical updates or trivial tasks; you go to them usually because you need decisions to be made.

There is always some kind of "so what" and "what's next." Otherwise it's probably not a very effective use of time.

The other way to think about it is this: if you find yourself presenting to senior leaders, you are probably in a position where you're expected to assume some agency. You're not just holding your palms out and waiting for answers.

As a result? You should tend to have a bias towards action. As should any content you produce.

You don't need to have all the answers, of course. But you need a very clear sense of how leadership can help you – and what you need from them.

This might take the form of:

- ... asking for support (e.g. resources to activate your plan)

- ... pushing for a decision to be made (so you can move ahead)

- ... educating or myth-busting (to influence some future decision)

Every touchpoint with senior leaders is a valuable opportunity for you to deliver a call to action. Even if it's subtle. Even if it's laying the groundwork for the future.

There's an inherent bias towards action in these conversations.

And if you're not doing that? You need to rethink why you're taking up their time or attention in the first place.

OK, now let's flip this around, and talk about the actual characteristics of exec-ready (written) comms.

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

Principle #1: "Tight" is right.

One of the hardest things to do when it comes to crafting exec-ready comms?

Keeping things "tight."

What does it mean when you keep things tight? It means that you:

- Focus real estate on only what is most critical to your message

- Minimize any slides that are repetitive or duplicative

- Construct an effective and efficient storyline "flow"

- Cut down on unnecessary or tactical detail

Let's see this in action via an example.

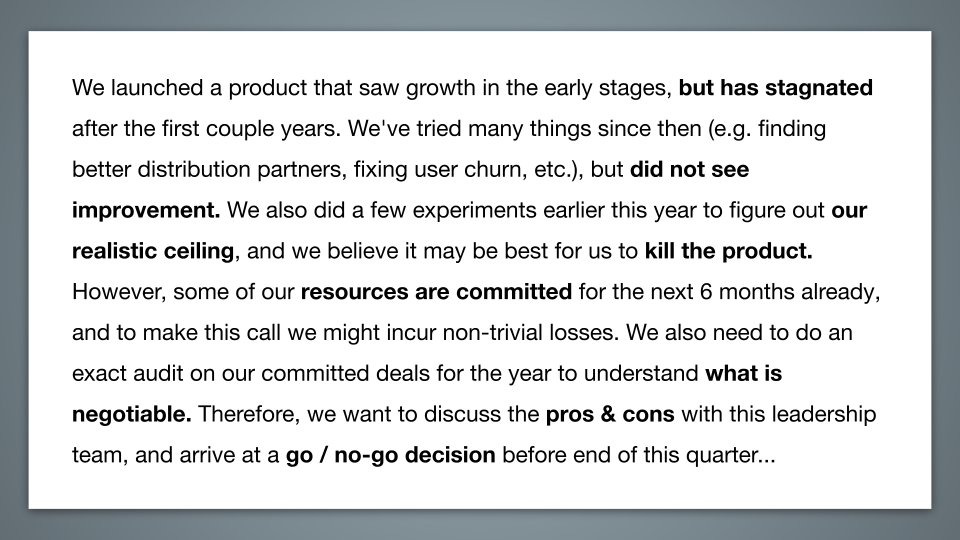

Imagine that you're planning to turn the following storyline into an exec-ready presentation:

While everything mentioned here appears to be fairly important – it's all over the place. You wouldn't want to create a presentation by simply building a slide for each and every talking point here.

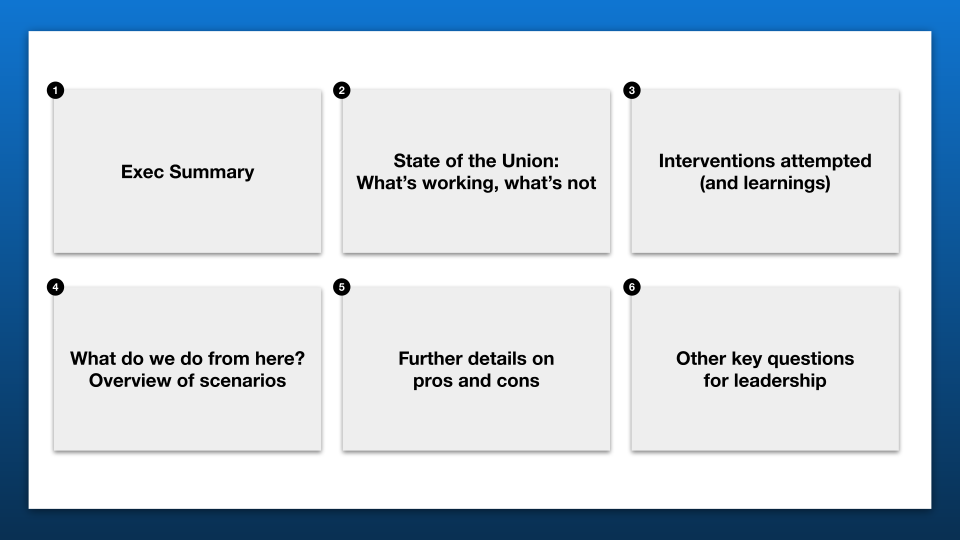

But people do that! Then their storyline ends up looking something like:

The problem? 15 slides in, we still haven't gotten to what actually matters! Meanwhile, we've had to deal with plenty of distractions and tactical details along the way.

This simply does not work. There is no intentionality when it comes to real estate use. Some slides encroach on one another. And the deck is being weighed down by too much detail.

No senior audience will have the time nor the patience for this.

By contrast, consider what an example of a "tighter" storyline could look like, if we cut and merge until we realistically can't anymore:

What do we see here? Well, it's clear that the backbone of our narrative really just comes down to a handful of slides here, which are all meaty enough to carry their own weight AND play a distinct role in our narrative.

(As for everything else? It simply becomes supplementary detail, which we can either punt or shove into the appendix.)

This is what we mean by "tightness." And the litmus test is this: anything less feels incomplete, and anything more feels inflated.

This is what executives are used to, and what they expect.

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

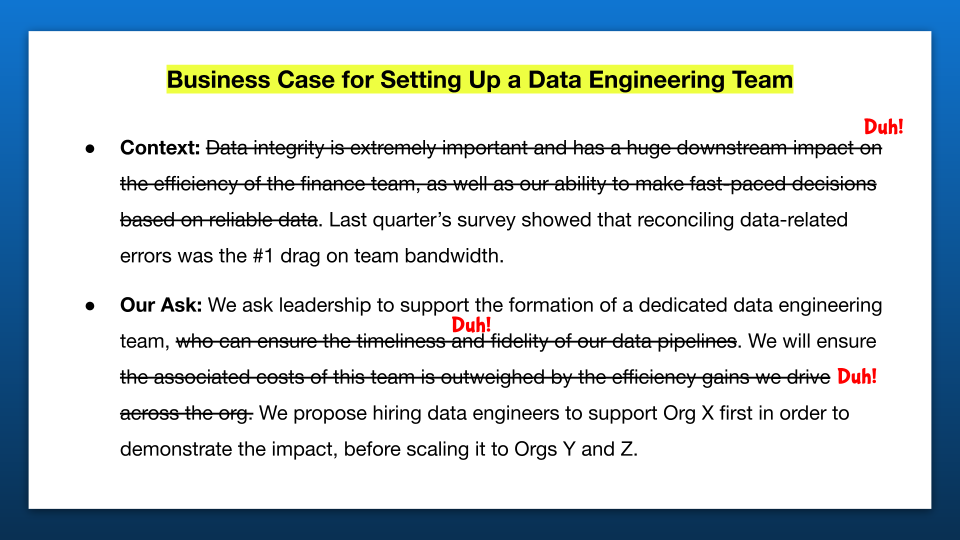

Principle #2: Use the "duh" test, ruthlessly.

One of the best ways to "tighten up" your writing? Use the "duh" test, ruthlessly.

What is the "duh" test? It's when you read what you write, and you ask yourself:

Would anybody read this and go "duh!" (or "no sh*t")?

If you've written something that no one would realistically disagree with – it's a waste of space (and your audience's time). Every occurrence simply becomes a cue for your audience to dismiss that section and skip ahead.

And the key to exec-ready comms? It's to cut out anything that fails the "duh" test, so that whatever you have left truly punches above its weight.

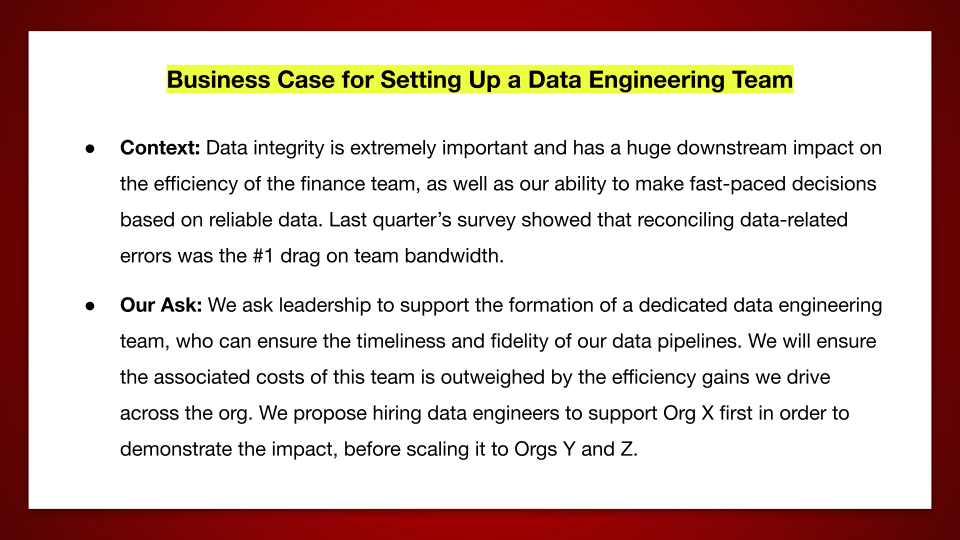

Let's look at an example here:

OK, what's wrong with this chunk of text?

Well, nothing is wrong technically – except 70% of it fails the "duh" test! It becomes an unfortunate waste of real estate (and hurts your credibility):

OK, so we don't want to waste time writing stuff that no one would realistically disagree with. Fair enough.

But let's take it one step further. Because the implied corollary of the aforementioned principle?

It's to bias towards writing stuff that is actually non-obvious, or can be challenged.

Because that means you're actually taking a stand on something – and that you're actually adding value to the conversation.

And in this example, we can see very clearly that:

- Last quarter's survey is an insightful datapoint, and is a critical motivating factor for this business case

- Proposing to prioritize Org X is a viewpoint that can be challenged (i.e. why not roll out all at once?) – but that means this is an actual point of view, rather than generic fluff

(Related: having a POV doesn't mean you have to be contrarian for the sake of it. Read my take on what having a strong POV actually means.)

Of course, you'll eventually run into situations where something that is obvious to you might not be that obvious for your audience. Or vice versa.

And that's fine. It just means that there's no one-size-fits-all guidance. You simply have to know your audience well, and tailor what you write accordingly.

It's tiring, sure. But it's a reflex for the best operators.

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

Principle #3: Simple and direct – yet precise

The best exec-ready comms are simple, direct, and crisp – yet incredibly precise.

Yes, we're asking for a lot here. We're hoping to have our cake and eat it too. But that's why achieving exec-readiness in written comms is so valuable.

Because if we don't put any thought into it? We might end up writing something like:

Without intentional acceleration and executive lean-in, our flagship product may struggle to see a decent growth trajectory, barring a change in macro conditions or competitive dynamics.

The problem with this? It's lazy thinking disguised with a bunch of corpspeak and buzzwords. Let's dissect it bit by bit.

- It's not "simple:" We have a very long sentence that is grammatically correct, yet mentally taxing to digest. There are also unnecessary and generic caveats ("barring a change in macro conditions...").

- It's not "direct:" We have a sentence that not only adopts a passive tone, but has also nested the key argument (= the concern on product growth) deep within the text. This is counterproductive.

- It's not "precise:" We have a sentence here that doesn't know what it's saying. Phrases like intentional acceleration or decent growth trajectory sound professional, but are ambiguous and generic.

So consider instead if we wrote like this:

"Our flagship product is at risk of missing user acquisition targets for the year. We suggest increasing marketing budgets by 20% as a one-off intervention, and we're seeking approval from this leadership group."

As a result? Simpler, more direct, and more precise.

The readability improves instantly – as will your ability to influence.