Are you really a generalist? Think again.

I've been a generalist for most of my career. And honestly, it's always made me a bit uncomfortable.

Why?

Because no matter how well I did at work, I would always worry about whether I "specialized" enough.

My worry was that if I didn't specialize, then I wouldn't be competitive.

And as the years went on? This sense of self-doubt would grow stronger.

Because as I started working with more tenured people, I would notice how specialized their profiles seemed.

For instance, these would be people that:

- ...specialized in a vertical (and thus deeply understood industry dynamics)

- ...specialized in a market (and thus owned an extensive personal network)

- ...specialized in technical skills (and thus seemed irreplaceable)

As for me? I was a generalist. The verticals I covered changed often. I even switched markets a couple times. I didn't feel like any of the above applied to me.

So ironically, even though I operated as a general-purpose strategist, who was supposed to solve any problem thrown at me at work?

I couldn't help but worry that I didn't actually possess any expertise. And that I didn't really pick up any specialized skills over the years.

And in today's issue – I'll explain why I couldn't be more wrong.

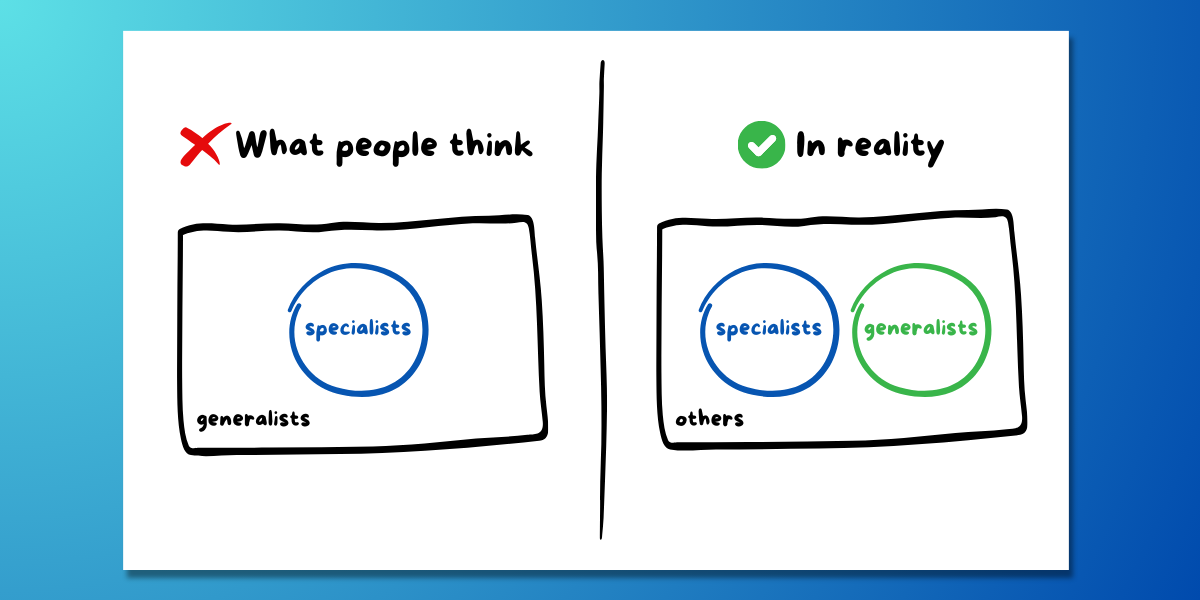

What people get wrong about generalists

Let me make one thing clear first.

There are people in this world who are clearly specialists.

And if you're not one of them?

It does NOT automatically make you a generalist by default.

Why? Because the generalist toolkit is anything but general. And the soft (and semi-soft) skills required can still have very steep learning curves.

In other words: it takes a lot to be a good generalist.

But what does this mean in practice, really?

The generalist toolkit, at a glance

Good generalists are hard to come by. And when you have them on your team, it can make a world of difference.

But just like no one is born ready to write code or calculate insurance premiums?

Neither are people just naturally good at being versatile generalists.

There are very specific skills that are required – and there is a clear checklist.

So while the following is by no means an exhaustive list?

Here's 3 questions to ask to get a sense of where you are on the journey of becoming (or continuing to be) an amazing generalist:

* This will of course vary by industry and role type. Your mileage may vary.

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

1/ Do you have a problem-solving toolkit?

The best generalist operators I've worked with tend not to be pigeon-holed by industry, market – or even job function.

Why?

Because they've developed a problem-solving toolkit that makes them extremely versatile – even if they're forced to tackle new subject matters.

Here are a couple specific examples.

☑️ Comfort with first principles thinking

What is first-principles thinking?

It means you approach problems by starting with fundamental truths or assumptions. You don’t simply assume. You're able to break down a problem into its basic components, and then reconstruct it from the ground up.

Being first-principles driven also means that you are trained to challenge assumptions and identify biases, ensuring there is airtight logic behind every decision (to protect the integrity of anything downstream).

And this is critical – if you want to be able to reason your way out of highly ambiguous or complex situations.

☑️ Ability to draw insight via pattern recognition

If you happen to specialize in a particular vertical, you might be able to get away with reflexes.

Because you know certain stats and metrics and ratios by heart. Your domain knowledge means that your gut feel can sometimes even trump someone's in-depth analysis.

And that's fine.

Except if you want to be a generalist? You need a structured way of drawing insight, without over-reliance on simply "having been around long enough."

You need a systematic approach that can help you recognize patterns (and more importantly, pattern breakers) – regardless of whether you're analyzing clicks or cokes or credit cards.

Related read: How to extract insight from anything

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

2/ Can you influence others?

Problem-solving is one thing. But you can't move the needle if you can't bring others along the journey.

The best generalists? They find ways to influence others around them, unite everyone towards one direction – and make things happen.

Here are a couple specific examples.

☑️ Ability to challenge leaders effectively

As a generalist, you often enjoy the privilege (or the challenge) of bringing in fresh perspectives to challenge incumbent viewpoints.

This is by no means easy – especially when folks on the other side of the table are tenured and senior.

The best generalist operators I see? They don't hold back from having a strong point of view simply because they feel like they're not "experts."

Instead, they know that challenging effectively is how they add value to the org – and they do it with radical candor.

Of course, just having the conviction to challenge is not enough. You need skills in order to surface dissent effectively – especially when there are egos in the room.

And that takes lots of practice.

For more on this: read my take on how to approach conflict, and how to tell senior leaders that they're wrong.

☑️ Ability to influence without authority

The best generalist operators don't only influence well. They also influence well without authority.

Because here's the thing: as a generalist, you might not always be the one calling the shots. But you're very often the only one who has a holistic view of everything.

(Meanwhile, other people are specialized – but often in their respective silos.)

What does this mean then?

It means that you are often in roles where you enjoy a unique vantage point, and can bring people together to either solve bigger problems (or to solve existing problems better).

But to do that? You have to work extra hard to help other people "see the light," without having any formal authority over them.

You're often working across functions (hence the term "cross-functionally") – and you're finding ways to influence, persuade, advocate, lobby, push, nudge...

...because you can't just simply dictate.

This takes tremendous skill. But it also adds tremendous value.

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

Can you bring order to chaos?

Last but not least: good generalists don't just function well when the problem is well-defined or ringfenced. They are adept at thriving in ambiguity as well.

How do they do this? Here are a couple examples.

☑️ Mastery of verbal and written comms

The hardest problems require a village to come together.

And you cannot bring the other "villagers" together – if don't know how to communicate effectively.

The best generalist operators I see? They get taken seriously because their comms (whether verbal or on paper) are extremely polished.

They do things like:

- Communicate sharply (without losing nuance or precision)

- Build insightful presentations (that are tight and exec-ready)

- Write solid strategies (that balance storytelling with actionability)

I have worked with fantastic people who have failed to make things happen, not because they didn't work hard. And not because they didn't know what they were talking about.

Sometimes, it was just because they communicated poorly.

* For more on this topic, check out the "sharpening personal comms" section in my newsletter archive.

☑️ Mastery of Output Frameworks

We talked earlier about the importance of being able to solve a wide variety of problems, by leveraging first-principles thinking, and a systematic approach to uncovering insight.

But all of that becomes a moot point, if you do not know how to properly land it with your stakeholders.

To bring order to chaos, you need good output frameworks. You need to find a way to bring others along the journey – and help them see what you see.

The best generalist operators I know? They find ways to simplify things using various mental models and frameworks.

They're not satisfied with having an answer and feeling smart about themselves. They find ways to make it easier for others as well.

Framework-based thinking takes lots of practice – but it is a skill that helps really good generalists scale their impact and extend their influence.

Related: I cover some of this in the "output frameworks" section of my StratOps playbook (95+ pages and 6000+ downloads!). You can grab it for free.

Quick Takeaways

- It's really hard to be a good generalist – but it can be learned

- Good generalists tend to be first-principles thinkers, and have systematic ways of extracting insight

- Good generalists tend to know how to challenge leaders effectively, and influence stakeholders without formal authority

- Good generalists also tend to be great communicators, and can bring order to chaos with strong frameworks and mental models