🧠 The Two Types of "Trust" at Work.

Most people only know of the first one.

When's the last time someone at work told you something to the effect of:

Don't worry, go ahead and drive this project as you see fit – I trust you.

If it was recent, I bet it felt pretty good!

Here's another question. When's the last time someone told you:

"I can't trust you fully yet – so until then, I'm going to be pretty prescriptive with what we need, and I'll check in with you every day to ensure you're on the right track.

Something tells me it's never happened (definitely hasn't for me). So I assume that means one of two things.

- All of us have perfect trust from our manager or colleagues.

- Either that... or the onus is on us to realize what actually happens when we do NOT have people's trust.

(Because they definitely won't be telling us straight up!)

Trust = Tablestakes.

Commanding trust at work is not something that's good-to-have. It's tablestakes. You simply cannot afford not to have trust.

Here are some things that might happen if you cannot be trusted:

- You will tend to be micromanaged. And no one (on either side) has ever enjoyed that experience. More tax for you; more tax for the person managing you. Hardly a win-win.

- You won't be trusted to lead projects that matter. Which means you cannot demonstrate your ability to lead projects that matter. And on goes the spiral.

- You won't get to make judgment calls. Which means your sense of ownership will be weak. And it is very hard to do good work without being motivated by the sense of true ownership.

- You won't always get the context you need. And yet context is critical in so many situations for knowledge workers, and can be the difference between endless churn vs. 80/20 solutioning.

OK, seems straightforward enough. But this is not the kind of trust we're going to talk about today.

Because, in fact, there's another way to think about it.

A Different Way to Think about Trust

There's two ways to think about the concept of "trust" at work.

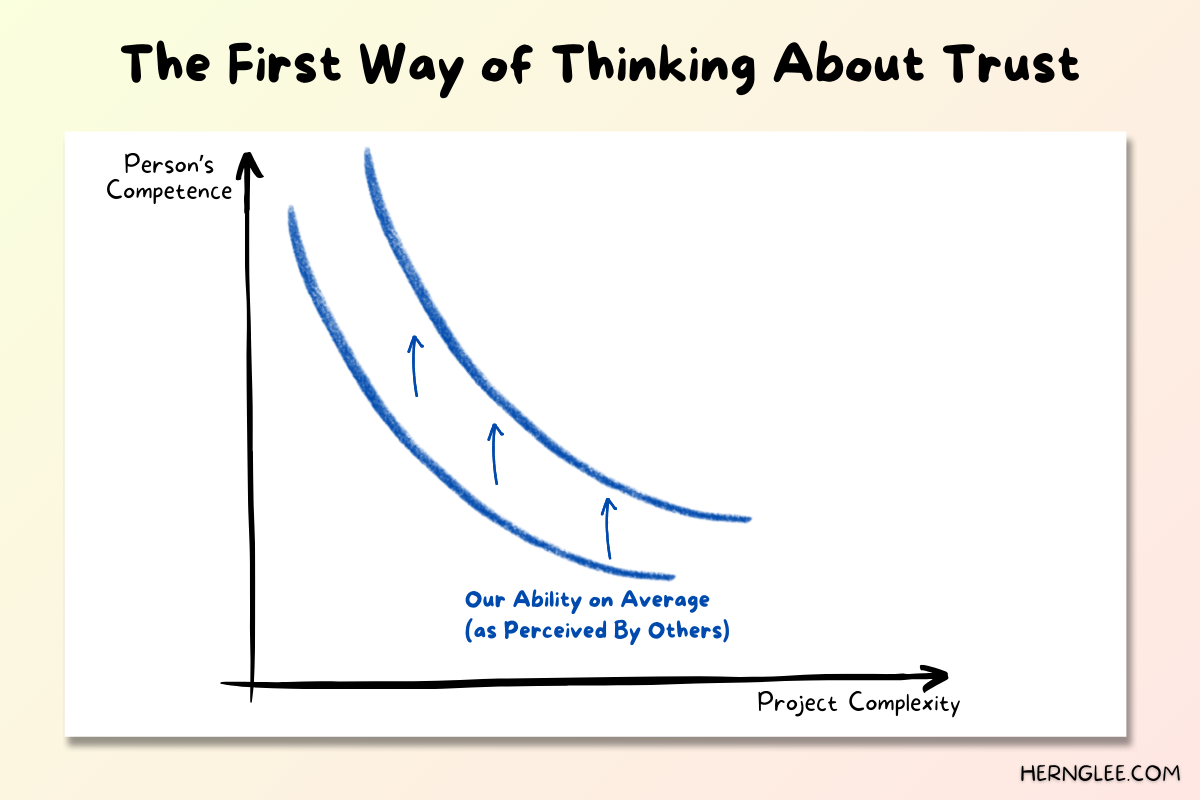

The first way is rather simple. It's also what comes to mind for most people. Trust tends to scale proportionately with your competence level; thus the more competent you are, the more trust you tend to command.

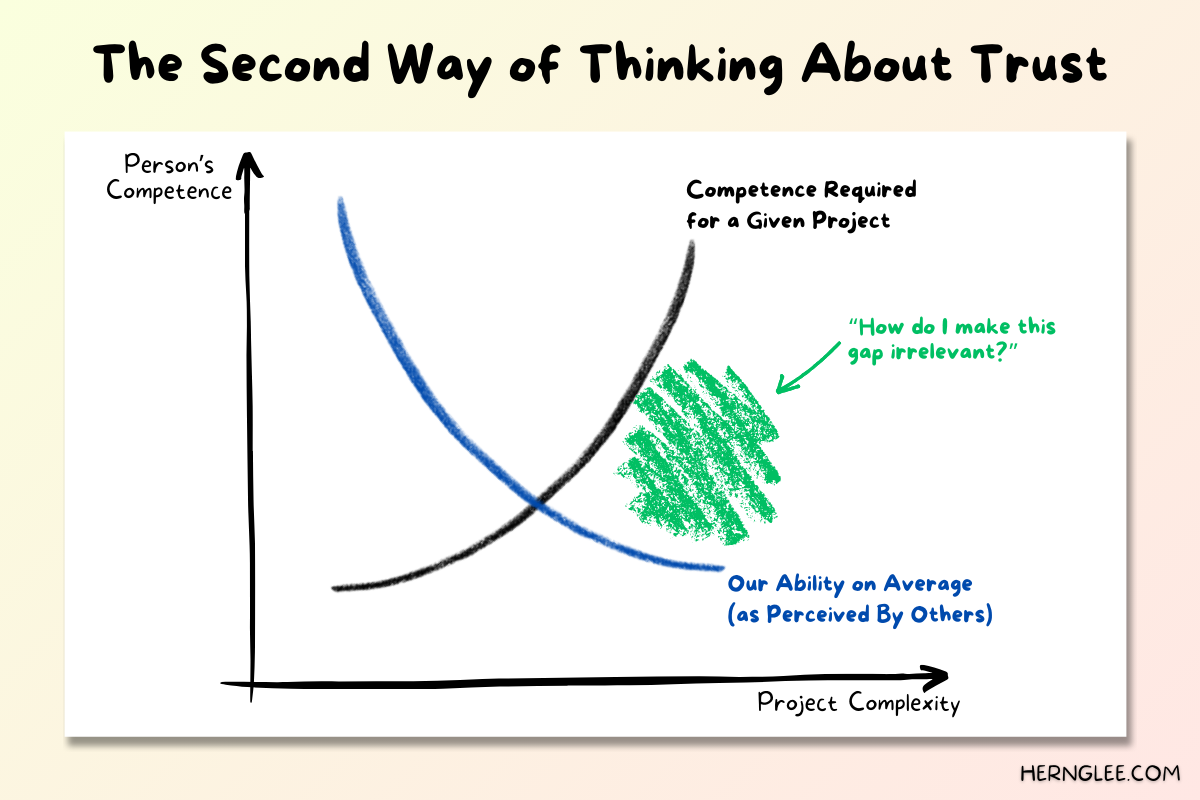

The second way to think about trust is more nuanced.

In this mental model, we're not just concerned with how competent you are. Rather, we care about how much trust you can command when there is an expected competence gap.

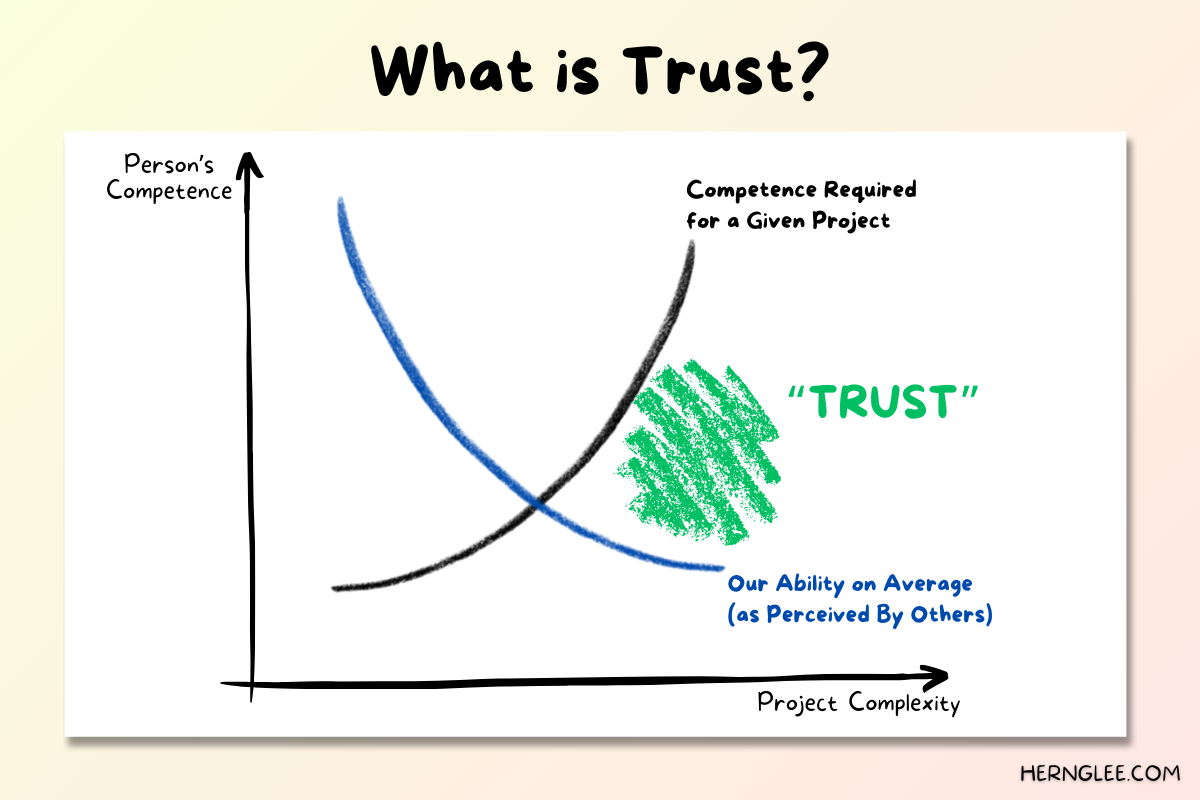

Here's how to think about it using a very scientific-looking* mental model:

Here's the thing. You can certainly command trust by ensuring you are perceived to be as competent as the task requires. But that will only take you so far.

To go farther, you want to think about how you command trust, even when others expect you to be outside of your comfort zone.

This is a much more interesting concept of trust. It measures the delta between how much people expect you to perform on average, versus the competence they need. It doesn't simply ask:

"How good are you on average?"

Rather, it asks:

"How likely are you to punch above your weight?"

It also forces us to ask: What am I doing to plug that "trust" gap?

👋 Subscribe for free to get Herng's newsletter directly in your inbox.

The Difference is Subtle

The two ways of thinking about trust are not mutually exclusive. In fact they're quite complementary to each other.

However, there's a subtle difference. The first way focuses more on raising our perceived competence level through establishing a strong track record. You can think of it as "pushing up" the blue curve:

On the other hand, the second way of thinking about trust recognizes that there will ultimately be challenges that we haven't encountered before, but that we can and should find a way to "punch above our weight."

More importantly, we want others to recognize our ability to do so. We want them to trust us – even if they haven't had enough datapoints from the past.

This is what we mean when we talk about bridging the "trust" gap. The objective is not to have solved every problem ever in order to gain trust (that sounds quite tiring and would take a long time).

Rather, somewhat paradoxically, it's to show that you have the toolkit in place to help you punch above your (perceived) weight.

An Underrated Way to Bridge the "Trust" Gap

Let me be clear: There are many ways to bridge the trust gap. Demonstrating a strong track record helps. Having people who like you helps. Marketing yourself better also helps.

What is often underestimated, however, is the value of first-principles thinking, and how it helps bridge the trust gap.

Here's what it means to be first-principles driven.

It means you approach problems by starting with fundamental truths or assumptions. You're able to break down a problem into its basic components, and then reconstruct it from the ground up.

Being first-principles driven also means that you develop a knack for challenging assumptions and identifying biases, ensuring there is airtight logic behind every decision (to protect the integrity of anything downstream).

If this makes sense to you – skip to the section below the fold. Otherwise, the example below illustrates the concept of first principles thinking.

First Principles Thinking: A Case Study

Imagine that you own an ice cream shop, and you've hired a store manager to run the business for you.

One day, your store manager comes to you with a proposal: he wants to develop five new unique ice cream flavors, and is looking for your approval (and money).

At a glance, this seems like a reasonable proposal. But if you were first-principles-driven, you might engage in the following conversation:

You: OK, what are we trying to achieve by developing new ice cream flavors?

Store Manager: Well, we want to invest in new flavors because it’ll help us attract new customers.

You: How do we know that?

Store Manager: I also run a pizza shop on the side, and whenever we come out with new flavors, we see first-time customers show up.

You: But does that translate to the world of ice cream?

Store Manager: Fair point. Maybe, maybe not.

You: Fine. And why are we trying to attract new customers?

Store Manager: …to make more money, of course?

You: Even if new flavors do attract new customers, why would that make us more money?

Store Manager: Because more customers means more sales?

You: For how long? How do we know these new customers will keep coming back?

Store Manager: Fair point, we don’t. But we can look at some of our past customer surveys to gain some insight.

You: Fine. And why do we want more sales?

Store Manager: Because it’ll bring more profits?

You: How do we know that? New flavors tend to have lower profit margins. What if a lot of our existing customer base starts opting for lower-margin flavors instead?

Store Manager: Fair point; let me rephrase. I’ll go back and run the projections to see if we’ll take a hit on overall margins. But I want to emphasize also that the goal is not necessarily to make more money in the short-term, but rather to tap into an older demographic who prefer less sugar intake.

You: OK, now we’re talking. But why are we trying –

Store Manager: …to attract these older folks right? Say no more, I get it now. Well, we’re losing a lot of business to the store across the street, because many parents prefer its low-calorie selection and would rather take their kids there. If we can attract these parents with our healthier new flavors, we’ll more than make back our money from the additional ice cream they buy for the kids. You know what – I need to redo this plan. Let me pitch you again in a week.

First principles thinking is hard. But it is incredibly valuable, because it suggests that you can be thrown into almost any situation – some of which might be above your "weight class" – and yet bootstrap yourself into figuring out the right path ahead.

First Principles Thinking, in Practice

Here's what it looks like when someone adopts a first-principles mindset.

- They enjoy the freedom to do things their way. They simply align on guiding principles with their stakeholders, and are trusted to find a way to get there.

- They are not intimidated by new challenges, as they can break down situations into simpler components, and then problem-solve using pattern recognition.

- They tend to get more opportunities. And when they deliver, they prove themselves further – and get even more.

So how do we get there? How do we become more first-principles-driven and bridge part of that "trust" gap?

Here are 3 practical tips.

#1 Ask "why" a lot. Then ask "why" again.

Start by asking "why" a lot. Ask yourself what assumptions you've made behind every claim or decision. Most of the time we bake implicit assumptions into what we're saying without realizing it's simply a function of lazy thinking.

Of course, there's nothing wrong with jumping to conclusions sometimes. After all, that's the value of experience. But the more you can demonstrate your ability to challenge assumptions, the sharper a thinker you become, and the more problems you can crack.

And the more trust you'll gain.

#2 Break things down. Then apply pattern recognition.

People who are adept at breaking problems down into smaller building blocks tend to thrive in the face of ambiguity. They train themselves to deconstruct problems until they're able to recognize patterns.

For instance, you might not know how to build a car. And you might not know how to build an engine. But you know it involves turning energy from one form to another – and that's a concept that's way more palatable.

Then all of a sudden, at least you have something to grasp at.

People who are good at solving problems know how to simplify and identify patterns. This helps them gain the trust they need to take on new challenges without always having demonstrated the corresponding track record.

#3 Bring people along the journey.

A lot of people think of the process of earning trust as simply taking a brief, executing, and reporting back great results. Then keep doing more of this. That's good, but not great.

A better way of approaching this is to keep the people that matter (e.g. your stakeholders or managers) in the loop – not on tactical updates, but rather how your decision principles are evolving due to new developments.

It is extremely valuable for people that matter to know how you approached a tricky problem, in addition to what you delivered at the end. This gives them the confidence that whatever success you delivered is likely replicable.

Plus, it serves as a great forcing mechanism for you to think through the meta-strategy behind your decisions and ensure there is the utmost clarity.

First principles thinking won't solve everything. It also won't teach you how to build a car from scratch. But it'll help you gain the trust you need to punch above your weight.

And you'll run a bit faster in your career as a result.