9 Lessons from 9 Years at Google

On the eve of reaching 9 years at Google, I decided to write down 9 of my favorite lessons learned over the years.

#1 You're always interviewing.

When I first joined Google, I thought passing the interviews was the hardest part. After all, my own process took several months and required more than half a dozen interviews.

I was partly right – the interviews were indeed tough.

But I was also wrong. Because it's easy to say the right things in 45-minute blocks a few times. It's much harder to maintain that discipline everyday even after you get the role, and treat everyday as if you're interviewing.

Here's why I believe this is important:

- Your track record matters. Google provides (and expects) people to take on new internal opportunities once every few years. And when you interview internally? Your reputation matters. You don't build that up overnight.

- People are always watching. And I don't mean this in a cynical way – in fact quite the contrary. Because we all know the folks who "show up" and give 100% everyday. We also know the folks who act the same way whether or not the boss is watching. Those are the folks that people vouch for.

Operating as if you're interviewing everyday doesn't mean you're "faking it" everyday. Nor does it mean you live in fear, thinking that everyone around you is secretly judging.

Instead – it just means that you operate with high conscientiousness. You work hard every day not just to earn the right to be in your current role – but also to lay the groundwork for future opportunities.

There's no such thing as cruising if you're playing the long game.

#2 Optimize for long days that feel short.

I've had my fair share of good and bad days at Google. Interestingly enough, they weren't always correlated with how busy I was at work.

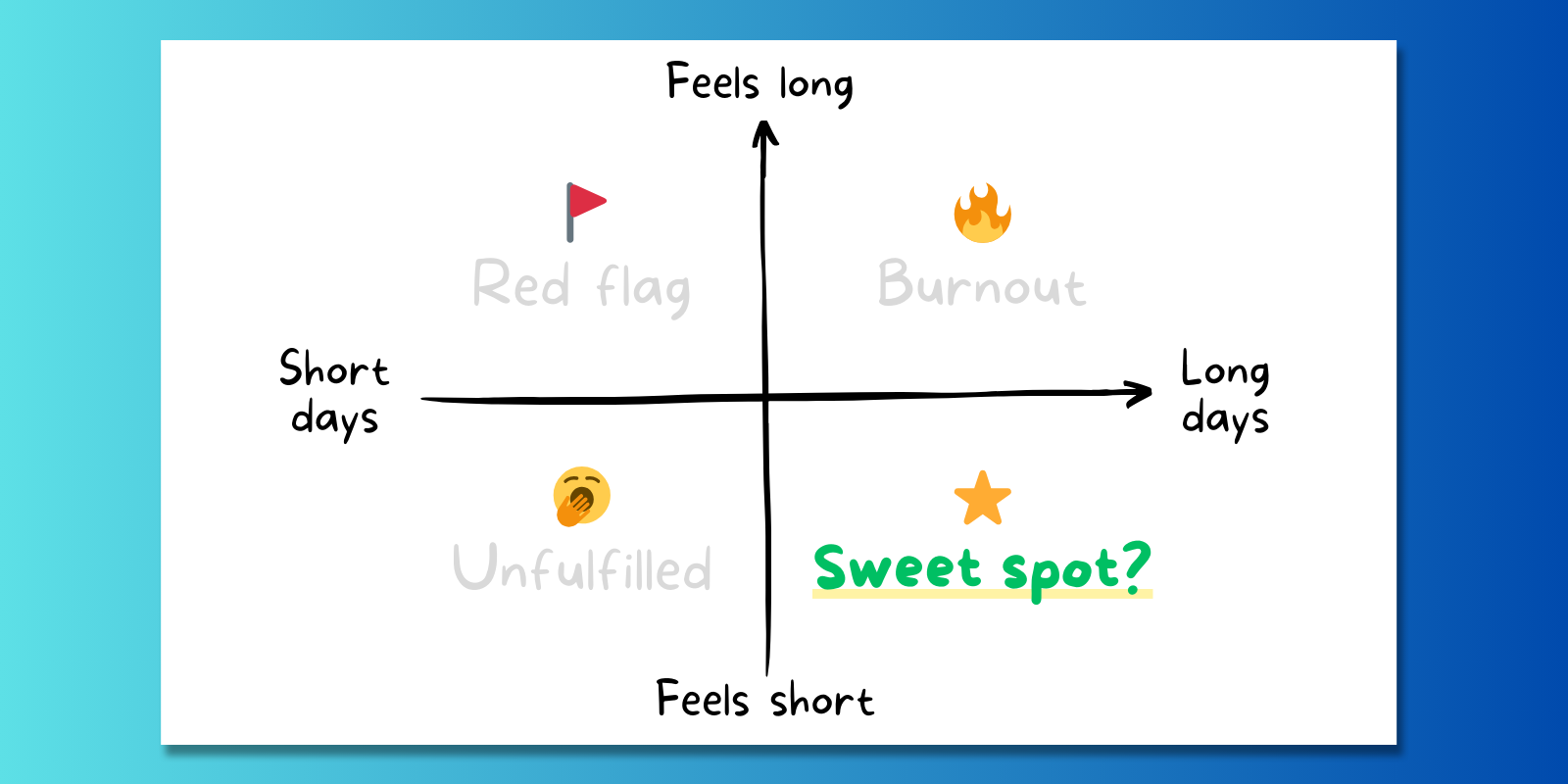

Instead, I realized that my energy level (and overall motivation) was often defined by the following framework:

It turns out that my "sweet spot" doesn't necessarily come from having a chill week or an easy day.

Instead, I find myself at my best when I go through long days that "feel short." This tends to happen when I'm highly motivated by my work, and when I enjoy a lot of autonomy.

On the other hand, I've learned that there are several kinds of "bad days," for example:

- Short days that feel short (= unfulfilled): Having days like these every now and then is totally fine. Too many of these can make you feel unfilfilled.

- Short days that feel long (= red flag): We all know what it's like when the workload is light, yet the clock seems to tick extra slowly. For me, it's a clear red flag when this happens too often.

- Long days that feel long (= burnout): Workaholics (or sadists) might find this scenario soothing, but for me it is always a sign to slow down.

My takeaway is this: Your happiness (or lack thereof) probably isn't defined by how much time you spend at work. Your well-being and work-life balance don't come from simply cutting down on work hours.

Instead, think about what makes a day feel "long" or "short." That's usually the best litmus test.

And when it feels long for too long? Then it's time to start asking yourself why.

#3 Ignore vanity metrics.

I had a coffee chat with a Google colleague years ago, where he called out the dangers of chasing "vanity metrics."

It was the first time I had ever heard of the term – and it has stuck with me ever since.

Here are some examples of "vanity metrics" at work:

- Title

- Team size

- Leveling

- Money

It's not that these things don't matter – it's just that they cannot be your northstar. Unfortunately, because they're easily comparable, they end up taking up most of our mindspace.

Meanwhile, things that are less comparable but far more important include:

- How fulfilled and energized do I feel?

- How much skillset growth am I gaining?

- How much impact am I creating?

It is in the nature of competitive people to constantly compare, benchmark, and judge. There's nothing wrong with that.

Just don't let the pursuit of vanity metrics dictate all the decisions you make.

#4 Trainings don't help (but stealing does).

Right before I started my job at Google, I remember asking a current Googler the following question:

"Are there a lot of trainings?"

You see, I was genuinely worried. I knew very little about the industry, and I was worried about my knowledge gap.

And I figured that surely the way to close that gap would be to attend as many trainings as possible.

But 9 years later, here's what I've realized: my greatest source of growth did NOT come from trainings.

Don't get me wrong – I've attended many trainings and taken many courses over the years – but they pale in comparison with what I learned by "stealing with pride" from the people I work with.

This includes:

- Being in the room with great leaders (and hearing the logic behind how they make decisions)

- Working alongside talented colleagues (and copying how they solve problems)

- Discussing my ideas with other Googlers (and getting them to poke holes and sharpen my thinking)

My takeaway is this: working with (and working for) the right people tends to trump everything else.

The corollary to this is equally important. Which is that if you run out of stuff to "steal" from people around you? Then it's time to make a change.

#5 The "S" word is not dirty.

I've always somewhat detested the "S" word – it's always made me feel uncomfortable, icky, and even a bit dirty.

I'm talking about selling.

My first role at Google involved meeting clients and doing soft pitching. It was never my favorite activity. It felt disingenuous and awkward to be asking for money.

But over the years, I learned two very important lessons.

The first lesson is this: Selling is only icky (and rightfully so) if it fails to benefit the other side. By contrast, the "right" kind of selling starts with asking what problems you can solve for your client, partner, or stakeholder.

Then you have every right to pitch in the hopes of achieving a win-win outcome.

The second lesson is this: you're always selling – even internally. I realized this after I took on an internal-facing role at Google, and still found myself doing all sorts of "selling." For example:

- Pitching the insights I uncovered from my analysis, in order to push for a certain course of action

- Explaining my problem-solving approach, in order to gain support from my manager

- Convincing my stakeholders the benefits of a certain new process, despite requiring more effort from them

Selling isn't dirty. You're always selling. You just have to do it with the right outcome in mind.

#6 It's not just skill versus will.

The Skill-Will Matrix is a simplified framework that segments performance based on two dimensions:

- Ability/capability (i.e. skill)

- Motivation (i.e. will)

The best performers then, obviously, are those that are both high-skill and high-will.

But I believe there's a missing dimension to this.

Because while "skill" and "will" are important when it comes to enabling performance, they're not enough. You also need the right enablers around you to unleash your potential.

In the spirit of rhyming, I call it "pills."

Much like vitamins, they won't make a difference by themselves. But without them? You'll likely struggle to perform at your best.

This includes things like:

- Do you have a manager who empowers you to succeed?

- Do you have colleagues who are collaborative?

- Are there the right tools or processes in place?

- Are you hampered by red tape or internal tax?

Don't underestimate the importance of having the right "pills" at work.

They may not be a gamechanger, but they can easily be a dealbreaker – even for top performers (related: read my take on how top performers make others better).

#7 Beware of the "platform" trap.

Working at Google over the years has opened up a lot of doors for me. But it's also made me acutely aware that not everything coming your way is because of you.

You see, a lot of people mistakenly attribute their success solely to their own efforts. They forget the tailwinds they've received (and continue to receive) from things like:

- Their company's brand name

- Their manager's influence

- The power of their leadership

- The resources of their company

All these things are platforms. They're vehicles that allow you to run faster than others. They're fulcrums and planks that give you disproportionate leverage.

But the question is this: What happens when you're on your own? What value can you bring once you no longer have the platform (e.g. your company) to depend on? How do you establish your credibility?

So maximize the leverage you're getting from your platforms.

But remember to lay your own tracks also.

#8 If it's not extreme ownership, it's not enough.

Extreme ownership is hard – but the best operators swear by it. And it was one of the most important lessons I learned at Google (related: read my take on how extreme ownership determines your success).

Early on in my career, I tended to conflate the notions of responsibility with ownership. But the two couldn't be more different.

Demonstrating responsibility is passive. You take a brief, execute, and move on. Don't get me wrong – you can still be fantastic – but usually only at executing tasks.

Demonstrating ownership, on the other hand, is different. You focus on achieving the objective – not just the task at hand.

One of my favorite stories at Google came from a VP, who once shared this story that happened early on in his career.

At the time, he had identified an important problem with an external partner, and he flagged it to his manager at the time. So he finished his spiel, expecting to get brownie points for his foresight.

But his manager simply asked:

“…So why haven’t you tried to solve it?”

The message was clear: it’s good to identify problems, but it’s not enough. Extreme ownership means you go the extra mile and think about what you can do to solve it (or who you need to tap on for support) – as if you truly owned the problem.

#9 Ambiguity is here to stay.

When I first joined Google, things were slightly less structured than I expected, but still mostly well defined. I knew what I was supposed to be doing (for the most part) – and I knew how to go about it.

But as the years went on? Both the what and the how somehow got blurrier as well.

So instead of being given well-defined project briefs – I was now expected to identify the right problems to solve.

And instead of driving projects with clearly defined outcomes? I was expected to deal with more and more projects with shifting goalposts.

Ambiguity was everywhere. And truth be told – I was often frustrated. It took a lot of practice for me to stop running away from ambiguity – and to eventually start embracing it (related: read my take on how to tackle ambiguity at work).

I'm still learning, but here's the takeaway: ambiguity is here to stay. The further along you are in your career, the more you'll be expected to thrive in ambiguity.

It doesn't mean you need to have figured everything out.

But you need to be comfortable with being (slightly) uncomfortable.